When the economy tanked last year, China seemed to be weathering the storm better than most industrialized countries. But a look at China’s migrant population tells a different story.

An estimated 23 million Chinese migrant workers—coming from the countryside to the city—were laid off as a result of the drop in exports, representing one of the largest casualties of the crisis globally. Migrants have been particularly vulnerable, says Kam Wing Chan, professor of geography, because of a Maoist-era institution known as hukou that continues to function in China today.

Hukou, a system of residency permits, was used by the Communist Party beginning in 1958 to minimize the movement of people between rural and urban areas. Chinese citizens were classified as urban and rural based on their hukou; urban residents received state-allocated jobs and access to an array of social services while rural residents were expected to be more self-reliant.

Not surprisingly, the disparity led many rural Chinese to migrate to cities, which in turn led the government to create more barriers to migration. “By law, anyone seeking to move to a place different from where their household was originally registered had to get approval from the hukou authorities,” says Chan, “but approval was rarely granted. In essence, the hukou system functioned as an internal passport system. While old city walls in China had largely been demolished by the late 1950s, the power of the newly created migration barrier is likened to ‘invisible’ city walls.”

The surprise is that the hukou system still exists today despite the stunning changes that have taken place in China over the past few decades. Some migratory controls were lifted in the late 1970s, in response to a demand for cheap labor in urban factories, but the basic structure remains intact. Rural-hukou Chinese who migrate to cities are not eligible for basic urban welfare and social service programs, including public education. To receive an education beyond middle school, they must return to their home village, despite a lack of funding for schools in the countryside and a bias against admitting students from rural schools to Chinese universities.

“There are still 600 million people treated very differently in China,” says Chan. “There are two levels of citizenship.”

The financial crisis has increased awareness of the problem. When factories closed last year with no warning, leaving workers unpaid for months, migrant workers had little protection. “They were the ones who got hit first,” says Chan. “They sit at the very bottom of the global supply chain.” Those affected were angry enough to protest, frequently and vocally, despite the risks. The potential for the situation to become more explosive definitely exists. “I think the central government is very aware of that,” says Chan. “So far, the government has been very restrained in dealing with protesters.”

How has China been able to continue to enforce the hukousystem? And why would it choose to? One obvious reason is that rural-hukou migrants represent a huge pool of cheap labor for factories producing products for export and are crucial to China's strategy of becoming the "world's factory." Low-cost migrant laborers who staff restaurants and shops also lower the cost of living for urban residents. And migrants work as nannies and maids for the urban Chinese middle class, who are loath to give up such luxuries.

“There’s a lot of vested interest in keeping the system as is,” Chan explains. “There’s no major incentive for anyone who has a voice to change the system. The Chinese middle class is not very progressive in this sense. This works for them, from a selfish point of view.”

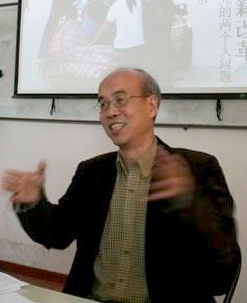

Chan, born in mainland China but raised in Hong Kong, has studied the hukou system for years and has recently given a number of public talks on the inequities. He believes that reform of the system is one of the top issues that China currently needs to confront. “I’m trying to give these people more of a voice,” he says, adding that American consumers may share some responsibility for letting this situation continue by demanding cheap products from China without questioning the cheap labor required to produce such products. Of course, many American corporations also make a lot of money from China's cheap labor.

“China cannot be continuing to do all this low-cost production,” says Chan. “It’s not the way out. There were great merits for doing that in the 1980s, but continuing it today is not the right strategy. They should let people gradually move into the city, get an education and social services, and focus on producing better products rather than just cheap products.”

Chan’s prediction for reform of the hukou system could best be described as cautiously optimistic. “China is moving very, very slowly on some of these policies,” he says. “I’d love to see them be a bit speedier. But I do believe this kind of change is possible. I do believe it will happen.”

Other links:

"Urban Myth": An editorial by Kam Wing Chan in the South China Morning Post, August 24, 2011

"Making real hukou reform in China": An editorial by Kam Wing Chan in East Asia Forum, March 3, 2010

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Sports Obsession Inspires a Career

Thuc Nhi Nguyen got her start the UW Daily. Now she's a sports reporter for Los Angeles Times, writing about the Lakers and the Olympics.

A Healing Heart Returns

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.