Cellist Sonja Myklebust has visions of performing for a captive audience of lab rats. Her professors and classmates think she’s on to something.

The rodent concert might not earn Myklebust a gig at Carnegie Hall, but it could be a compelling final project for a UW course she’s taking this quarter, Art and the Brain. Offered through Digital Arts and Experimental Media (DXARTS), the course is co-taught by an artist, an art historian, and a neuroscientist who share an interest in the intersection between art and science.

“We’re interested in teasing out areas of mutual inquiry that will potentially generate knowledge in both fields,” says James Coupe, associate professor of DXARTS, who developed the course with Edward Shanken, visiting associate professor of DXARTS, and Eberhard Fetz, professor of physiology and biophysics.

Fetz met Coupe after admiring Sanctum, a public art project created by Coupe and DXARTS chair Juan Pampin for the façade of the Henry Art Gallery. Intrigued by the work’s provocative melding of art and technology, Fetz wondered whether a similar melding might be possible with art and neuroscience. That discussion led to the interdisciplinary course.

Most students in the class are working toward PhDs in DXARTS, though a few—including Myklebust, a doctoral student in cello performance—come from other disciplines. None are scientists, so Fetz started by outlining the basic principles of neuroscience. “It’s a huge field, so cutting it down to an hour-long presentation was a little superficial,” he says, understating the obvious.

Fetz, Coupe, and Shanken don’t expect the students to magically transform into neuroscientists, but they do hope the course content will inspire projects in which brain science is integral. “We’re not looking for them to go into the lab and actually know how to do neuroscience experiments,” says Coupe. “We’re just presenting them with ideas and asking, ‘What are some interesting things you, as an artist, could do with this?’”

Myklebust recalls being “immediately intrigued” when she heard that the course would explore contemporary art and performance through a neuroscience lens. “Since I spend most of the day using my brain while practicing music or stimulating a listener’s brain when performing music, I thought that this course was a great opportunity to learn more about the deep mystery that is our brain,” she says.

Shanken, an art historian and critic, argues that most artists intuitively explore many of the same brain-related questions as neuroscientists. “They are not trained as neuroscientists per se,” he says, “but they are deeply involved in exploring what perception is—what it is like to see and understand and experience things—in order to create experiences that somehow expand our understanding of the world.“

And yet artists and scientists come at these questions quite differently, which provides both challenges and opportunities for collaboration. Fetz believes that artists can creatively address scientific problems about the mind and brain, bringing ideas and methods that don’t exist within a traditional scientific domain. That belief, he says, is what inspired him to co-teach the course.

"By the end of this class, we'll have eleven proposals. And these are doctoral students at various points in their studies. So who knows? Maybe these projects will become their dissertations, maybe their life's work for all we know.”

Robert Blatt, a PhD student in DXARTS, isn’t sure that art and science can be reconciled—but he’s willing to give it a try. “The course has forced me to consider how my artistic methods could also function as scientific practice,” he says. “That being said, it has also made me question the value of such an approach, and the situated difference between scientific and artistic knowledge. Are these differences reconcilable? I don’t know.”

At the end of the quarter, each student is required to submit a proposal for an art project that incorporates neuroscience in a meaningful way. Blatt, a composer, proposes working with patients undergoing electrocorticography, an invasive procedure to treat intractable epilepsy. He plans to document changes in the patients’ emotional states during the procedure through interviews, monitoring of breath and heart rate, fluctuations of electrical activity in the patients' brains, and field recordings. While the audio materials would lead to an artwork, the documentation might also reveal “spatio-temporal neural correlates for emotion” that could be valuable to scientists.

Myklebust’s proposal involves her string quartet, Oceana. She envisions the quartet performing for an audience that is wired to record brain activity, with the performance evolving based on brain responses to the music. “I want to look at what makes music engaging to a listener and turn the role of listener into an active role as participant,” says Myklebust. Though she’d like to perform for humans, rats have advantages from a neuroscience perspective. “Reading human brainwaves and brain activation is challenging and can require invasive procedures,” she explains, “so we’ve thought about using rats and reading how a rat’s brain reacts to different musical stimuli.”

Whether any of the student proposals lead to actual projects remains to be seen. The faculty believe that having students brainstorm ideas is an exciting—and realistic—first step.

“It’s hard enough to make a good work of art that is artistically relevant,” says Shanken, “and it’s hard enough to design a scientific experiment that is relevant. But to try to join the two together within the context of the ten week seminar? So we’re not demanding that the students produce the actual experiment or the actual art object, but that they at least think through scientific and artistic problems in sufficient depth so that they can put forward a proposal for something that would be both scientifically and artistically relevant. That, in itself, is a tremendous challenge.”

Adds Coupe, “By the end of this class, we’ll have eleven proposals. And these are doctoral students at various points in their studies. So who knows? Maybe these projects will become their dissertations, maybe their life’s work for all we know.”

The three faculty know one thing for sure: they want to continue teaching together, with hopes of adding neuroscience students into the mix in the future.

“This course has been a very exciting collaboration because the three amigos here bring different expertise to the table,” says Fetz. “The three of us have bounced ideas back and forth, and we are working with very bright and creative students who have catalyzed a lot of interesting insights and discussions. So far, it’s been a great experience.”

More Stories

All the World's a Stage — and a Game

Students in DRAMA 480 learn how techniques used in game design can be adapted for interactive theater productions.

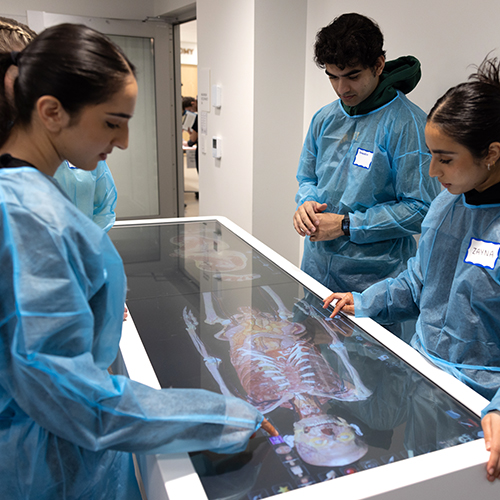

The Impact of Anatomy Lessons

Anatomy for Change, a program for students underrepresented in healthcare careers, provides opportunities to spend time in an anatomy lab.

Exploring Connections Through Global Literary Studies

The UW's new Global Literary Studies major encourages students to explore literary traditions from around the globe and all eras of human history.