Before taking six undergraduates to a remote Indonesian island to conduct research in August, Randy Kyes, assistant professor of psychology, tried to prepare them for what they would encounter. No running water. Primitive cabins. Rats. Cockroaches. Pit vipers. Lizards measuring up to seven feet long. But students still were shocked when they arrived on Tinjil Island, a small, tropical rainforest island southwest of Java.

"When I got there, I wanted to cry," recalls Catherine Chu, a psychology major. "I'd never seen anything like it before." Too rustic? Hardly. "It was just so beautiful," says Chu. "The entire time we were there, we were all amazed by it."

Chu and her classmates signed up for the Indonesian field study program--a month-long program offered by the Department of Psychology--to get a taste of field research. While on the island, they pursued individual research projects and took an evening class on primate behavior and ecology, taught by Kyes.

The program, introduced by Kyes in 1995, had an unusual genesis. Tinjil Island had been developed as a natural habitat breeding facility for longtailed macaques as part of a collaborative project between the UW Primate Center and the Primate Center at Indonesia's Bogor Agricultural University (IPB). Kyes, who had been travelling to Tinjil Island each year to supervise the operation and provide field training in primatology for students from IPB, soon realized that he could offer a field experience for UW students at the same time.

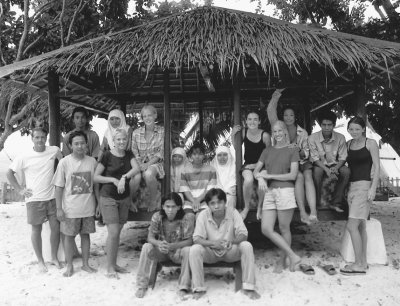

"The program lends itself to undergraduate education, and it evolved naturally out of our relationship with the Indonesian university," says Kyes. "It's the kind of opportunity I would have liked when I was an undergraduate." Thus began a collaboration between Kyes and Dr. Dondin Sajuthi, director of the Primate Center at IPB. Now UW and Indonesian students live and study together during their stay on the island. Entang Iskander, also from the Primate Center at IPB, assists Kyes with program activities.

By the time UW students arrive on the island, they have already taken a two-credit course with Kyes to plan their research projects and develop procedures for collecting data. This year, some students chose to focus on the island's insect species and its coral reef, while others worked with Kyes on a census of the island's longtailed macaques.

For hours each day, those conducting the census walked on island trails--using machetes to clear the fast-growing foliage--in search of monkeys. Encounters were recorded, including location, age and gender of the monkeys, and their general behavior. "We did this every day, traveling the same trails, to get a reliable picture of the location of animal groups, their size, and behavior," says Kyes.

The research had its challenges. "I had to learn to get past the bugs and the six-foot lizards and keep walking," recalls Chu. "And I had to learn how to hear and see in the jungle. At first it was difficult to differentiate the noises. There are four birds that sounded like monkeys for the first few days."

Kyes, who has directed this program for four years, realizes that there is a steep learning curve for the students. Although he requires them to complete research projects and write up their findings, he does not expect groundbreaking work.

"The project is intended to be a learning experience," he explains. "In a short period, it is impossible to expect too much. The first week is spent getting oriented, leaving only a few weeks for data collection. But the students do get a real flavor for what it is like to be out in the field. And their observations can contribute to our understanding of the biodiversity of the island."

For many students, field research is not what they expected. That's no surprise to Kyes. "A lot of people go over there thinking that field research is exotic and exciting," he says. "They discover that it can be drudgery and boring at times, with a number of hardships. This can help them decide if field work is something they want to pursue further."

After a day in the jungle--and often an afternoon dip in the Indian Ocean--the UW and Indonesian students would retreat to a classroom where Kyes lectured on primatology. As one might expect, the group was usually bursting with questions. "The course was really helpful," says Chu, "especially for those of us with no background in primatology. It was the only time each day when we were all in one place to compare notes on our experiences."

As the course neared its conclusion, students told Kyes they wished they could stay longer. Past participants have told him that it was the best experience of their undergraduate career. "It's a lot of work," says Kyes, "but it's rewarding to see students experience something so different for the very first time. I keep reliving that experience through my students."

Kyes' only regret is that some interested students are unable to participate due to financial constraints. The program cost, plus airfare, is more than some students can manage. "I hate the thought of this being an exclusive thing, only for those who can afford it," says Kyes. "One student sold a car so she could take the course."

Chu is one of the lucky ones. She received a Mary Gates Scholarship that covered her expenses and that is enabling her to continue her research with Kyes during autumn quarter. Although she has decided that she prefers laboratory research to field research, she is grateful that she had the opportunity to experience field study.

"It was an amazing opportunity," she says. "You'd think you would need to be a graduate student to participate. It's beyond what one could expect as an undergraduate. It's perks like this that make undergraduate education memorable."