In a studio filled with ceramic artworks, Timea Tihanyi concentrates on creating a porcelain vessel. Rather than hand-building the piece or throwing it on a potter’s wheel, she monitors a 3D printer that layers coils of clay to create an artwork based on her specifications.

The shelves of the studio are lined with more works built using a 3D printer, from round vessels with braille-like bumps on their surface to twisting towers of clay with intricate patterns of negative space. No two pieces are exactly alike; all reflect Tihanyi’s vision and careful oversight. “Ceramic 3D printing requires interaction,” says Tihanyi, senior lecturer in the UW School of Art + Art History + Design (SoA+AH+D). “You by no means push a button and then walk away.”

I can’t really make things with the 3D printer that would replace anything I would make by hand. But it gives us so many new possibilities that didn’t exist before.

Tihanyi first learned about 3D printing eight years ago, when she took a UW architecture course on digital fabrication, with support from a Milliman Award. “I thought I should learn about the technology because this is going to be the future,” she recalls, “but at the time I didn’t have much use for it.” What changed her mind was a summer spent at the European Ceramic Work Centre, a premier research center, where she had access to 3D printers for ceramics. After returning to Seattle, she ordered her own 3D printer and launched Slip Rabbit Studio, a place for experimentation. That was three years ago.

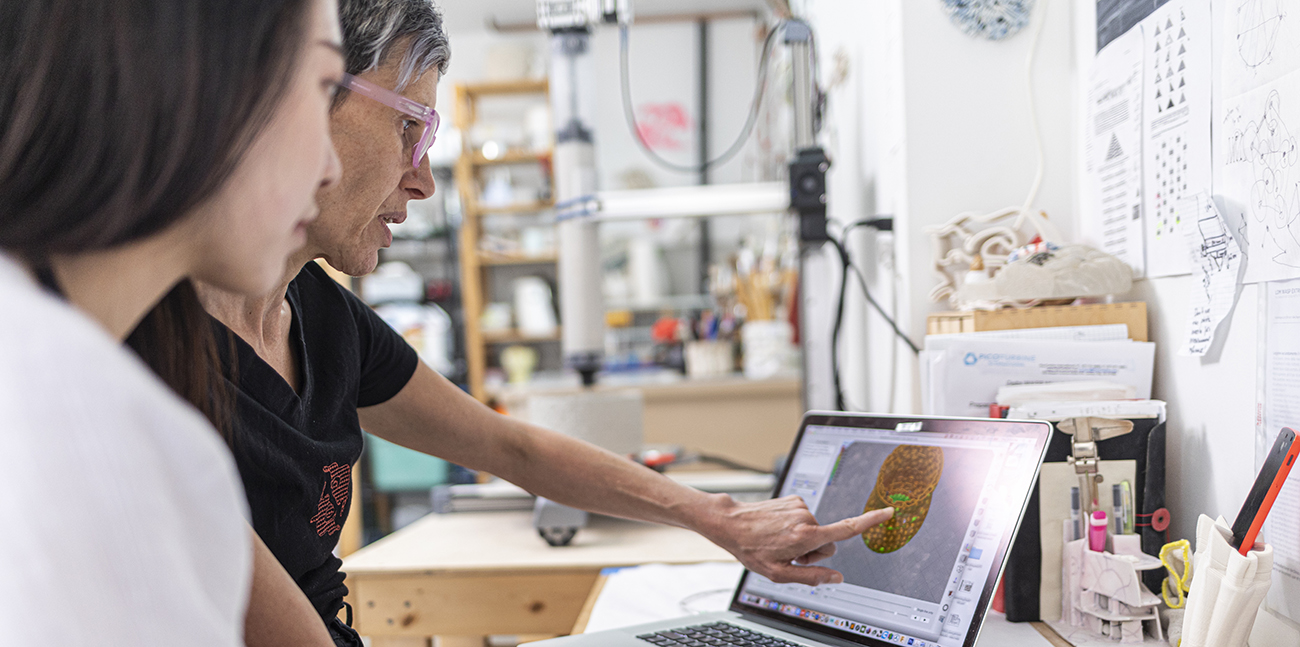

From the start, Tihanyi has invited student interns to join her in exploring the possibilities of 3D technology. “It’s like any other tool,” she says. “When you first use it, why would you know what to do with it to get the desired effect? That first year, it was a shared trying and learning. The students came to learn and problem-solve with me. I saw myself as a research director in a sense. Things that were interesting to me or to the students were the directions we took.”

An ongoing challenge has been the unpredictability of clay. The 3D printer extrudes a steady stream of clay using pressure, much like extruding caulk with a caulk gun. But moisture in the clay can vary depending on the weather, affecting how it behaves. And air bubbles in the clay can cause unanticipated hiccups as the material is extruded by the printer. Tihanyi embraces that unpredictability.

“3D printers were designed as production tools, with everything staying the same, but printing with clay is not like that,” Tihanyi says. “It’s not unusual for me to print something a few times to learn what the particular challenges (of the form) are. If I’m lucky, I’ll get one good piece. It’s not a manufacturing process by any means.”

What intrigues Tihanyi most about this technology is the potential for collaboration. In the past few years she has collaborated with SoA+AH+D colleagues and Department of Mathematics faculty, and has hosted more than a dozen undergraduate and graduate students from visual communication design, industrial design, mathematics, computer engineering, informatics, psychology, and other fields.

One collaborator, Audrey Desjardins, assistant professor of interaction design, has an interest in data gathered by smart technology in the home. She and Tihanyi became intrigued by the potential of turning sound data gathered from various settings—Desjardin’s home at night, a bustling restaurant—into a physical form. Using a 3D printer that continuously extrudes clay onto a revolving plate, Tihanyi programmed each sound level to pause the revolving plate for a specific duration so that clay would build up in certain spots. The resulting artworks have an intriguing irregular surface that gives physical form to the sound data.

Tihanyi also has collaborated with Sara Billey, professor of mathematics and John Rainwater Faculty Fellow. For their project, Billey and mathematics students translated discrete mathematical algorithms into complex two-dimensional patterns on the computer (leading to a master’s thesis for one student). Tihanyi then turned those patterns into textures using the 3D printer, with coding help from Daria Micovic (BS, Mathematics, 2018), a Slip Rabbit intern for two quarters. “Daria was very much on board with my thinking process,” recalls Tihanyi. “It was really fun to work together because we would say, ‘What if…?’ and go down the next rabbit hole.” The physical representations of what can be made with math and coding range from organic, twisting clay structures to intricately patterned raised dots on round vessels.

The collaboration with Billey was made possible through the Bergstrom Award for Art & Science, which supports faculty projects that enhance the student experience and bridge the intersection between art and science. “It is amazing that a donor would think to facilitate this type of collaboration,” says Tihanyi. The award helped cover the cost of materials, graduate student support, and Tihanyi and Billey’s time. “It gave us the impetus to have a research group throughout the year, with undergraduate and graduate students in mathematics and my art interns,” Tihanyi says.

Tihanyi and Billey have spoken about their collaboration in professional settings and co-presented a talk at the UW's annual Math Day in the spring. To introduce 3D printing to more students, Tihanyi offers a course, Maker Practices, Maker Cultures, through the UW’s Interdisciplinary Visual Arts program. She also offers summer workshops for educators at Slip Rabbit Studio.

Despite the interest, there are still those who criticize 3D printing in clay as a threat to the arts. Tihanyi wants to ease their minds. “There’s often a huge fear in any maker community that if a new technology comes in, it will take away something from the hand,” she says. “I don’t think it does that. I can’t really make things with the 3D printer that would replace anything I would make by hand. But it gives us so many new possibilities that didn’t exist before.”

One of those possibilities, which Tihanyi plans to pursue in the future, is creating 3D-printed forms that respond to subtle changes in the body or the movements of the person creating the work, through a process similar to the one she and Desjardins used to design with sound. Tihanyi hopes that people with varying physical abilities will be able to create unique ceramic forms through this technology.

“It’s something I’ve been thinking about, but I don’t have the know-how to make it happen yet,” Tihanyi says. Then she laughs. “There are so many things I want to do, and so little time.”

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.

Through Soil Science, an Adventure in Kyrgyzstan

Chemistry PhD alum Jonathan Cox spent most of 2025 in Kyrgyzstan, helping farmers improve their soil—and their crops—through soil testing.