It’s been a wild few months in American politics. Incumbent president Joe Biden withdrew from a reelection bid. Former president Donald Trump was the target of two assassination attempts. America remains embroiled in ongoing wars around the globe. To provide historical context for this moment in presidential politics, Perspectives newsletter spoke with Margaret O’Mara, professor of history and Scott and Dorothy Bullitt Chair of American History, on October 10, 2024.

Let's start with President Biden's decision to withdraw from the 2024 presidential race in July. Was that late withdrawal unprecedented?

Looking at elections from the 20th century onward — because the 19th century was a very different sort of politics — the closest precedent was in 1968 when Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not continue running for reelection. That was in late March, at the tail end of a long speech he gave about Vietnam, which was the issue that sunk his electoral chances. Johnson didn't like to lose and was getting contested in Democratic primaries, so he decided to drop out before he could lose anything. In contrast to Biden — who left the race after a painfully public “pressure campaign” from fellow Democrats — Johnson's announcement surprised many of his allies. Only those in his closest circle knew ahead of time about the content of his speech.

Vice President Kamala Harris replaced Biden as the Democratic nominee. Can you put her candidacy, as a woman and person of color, in a historical perspective?

One thing that was surprising given America's history of racial prejudice and ongoing racial reckoning is that we had an African American president in Barack Obama before we had a female one. Many women have run in the past, including major-party contenders like Margaret Chase Smith in 1964 and Shirley Chisholm in 1972, but it was not until 2016 and Hillary Clinton that we had a woman as a major-party nominee. If I had been making predictions — though historians do not like to make predictions — my money would have been on a conservative woman, an American Margaret Thatcher, becoming the US president first.

Speaking of Margaret Thatcher, women have served as president or prime minister in other countries for decades. Why not in the US?

The US presidency has been such a male-gendered role. That has been very persistent. But it’s also difficult to compare our presidency to other countries, because the United States stands alone in modern times as an economic and military superpower. The American presidency is the most important job in the world. It looms larger than being the president of Finland, for example. And our distinctive governmental structure — as compared to a parliamentary system, for example — overemphasizes and consolidates so much power in the hands of the presidency. So the US being slower to elect a woman doesn't surprise me.

It's notable that Harris has not focused on her gender or racial identity during her campaign.

I think Harris has tried to run a very different campaign than Hillary Clinton’s in 2016. Clinton was not successful when she leaned into her gender identity as a kind of counterweight to Donald Trump — though I don’t chalk up her loss to the electorate not being ready for a woman president. As a very familiar political figure who'd been on the scene for so long, Hillary Clinton was not able to present herself as the change candidate. Even though she was the first woman, she was seen by many as the status quo, the establishment.

Again and again, the person the electorate feels is making a better case for something new, for change, is the one who usually prevails.

Why is being a “change candidate” or political outsider such a selling point?

The allure of the political outsider, or someone highlighting their humble roots when making a case to become president, is a really old political trope. It goes all the way back to the very beginning, when Thomas Jefferson, an aristocrat, wore a ratty dressing gown in the White House to show that he was a man of the people. It would be like Biden or Trump wearing a hoodie all the time! Again and again since then, a humble background helped get you elected. That intensified from the 1970s forward, in the wake of Watergate and Vietnam, because there was great dissatisfaction with Washington insiders. We saw this vividly in the 1976 campaign when Jimmy Carter, a peanut farmer and governor of Georgia, beat out a big field of better-known Democrats who were Washington insiders. Again and again, the person the electorate feels is making a better case for something new, for change, is the one who usually prevails.

If change is so important to voters, why do incumbent presidents running for reelection usually win?

Under the right circumstances, even incumbents and Washington insiders have been able to present themselves as the change candidate. After Reagan's first term, there was still a kind of novelty about Reaganism and the conservatism he was representing, so he was the change candidate that year. In 2012, running for a second term, Barack Obama was still able to make a case that he was more about change than Mitt Romney. Interestingly, this year you have an ex-president promising a return to the ways things were — but who was the compelling change candidate in 2016 — and a sitting vice president who has positioned herself remarkably well as a change candidate, distancing herself from the current administration while also not distancing herself. It’s been a really fine line for Kamala Harris.

Were you surprised how quickly the Democratic party rallied around Harris once President Biden stepped aside?

During those weeks when Biden was resisting dropping out, the party had time to rally and coalesce. In an alternate historical scenario, had Biden decided to drop out a day or two after the debate, there might have been a very different process to find a nominee. There might have been more contestation. But instead there was a remarkable show of unity. I think that reflected the Democratic Party's great alarm at a Republican Party that had unified solidly behind Donald Trump again and again. The Democrats knew they needed to match that.

Spreading misinformation about one's opponent seems to be an accepted strategy in this presidential campaign. How does this compare to past elections?

There's always been mudslinging and smears and calling people names — you wouldn't believe what the Adams campaign called Thomas Jefferson in 1800 — but saying something that isn't true again and again and again and having no shame about it being wrong, even if you're being corrected, is something new. It's one of the things that makes Donald Trump and the current Republican party stand out from their predecessors. But it's not about one man alone. It's also a function of our information environment, where misinformation runs rampant and the firehose of information shoveled at everyone is being sliced and diced and taken out of context. Our brains are not designed to process this much information. It is really difficult to find the truth and follow the story. So the loudest and angriest and most outrageous voices are the ones that get the most attention.

We've always been an imperfect democracy that's trying to become more democratic and to live up to the founding ideals of the country.

Given your historical knowledge of the presidency and presidential elections, do you have any thoughts on how the pendulum might swing in the future?

There's been expansion and contraction. There have been crises and resolution. Right now, some of our institutions are not functioning as they should, in part because they are built on 18th-century frameworks that woefully need updating. We've got outdated software, so to speak. It's not that the US Constitution needs to be thrown out — it's a really good one that has endured a lot of stress tests — but it was designed to be amended, to be flexible and recognize the times.

I always like to end my classes with a little ray of hope, so I'll do that here. We've always been an imperfect democracy that's trying to become more democratic and to live up to the founding ideals of the country. For all the current skepticism and lack of trust in the US government, people still believe in the rule of law and a free press and free speech and basic constitutional rights that make us quite different from other places that have fallen into autocracy or total dysfunction. And so the hope is that we will continue to keep the faith — and keep voting.

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Sports Obsession Inspires a Career

Thuc Nhi Nguyen got her start the UW Daily. Now she's a sports reporter for Los Angeles Times, writing about the Lakers and the Olympics.

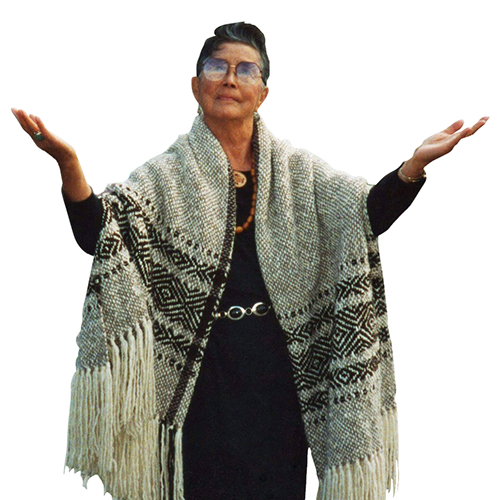

A Healing Heart Returns

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.