At Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, a patient lies on a gurney in a hospital gown. While answering questions posed by two UW Medicine neurology residents, the patient’s breathing grows labored and the residents must respond.

Across the hall, a 40-something mother and her adult daughter meet with another neurology resident to discuss the mother’s memory decline. While the daughter expresses concern, the mother makes light of recent memory lapses, chalking them up to depression, for which she is being treated.

Such scenarios are familiar for neurologists, but on this day they are simulations, with students from the UW College of Arts & Sciences' School of Drama performing the roles of patients and family members. Through simulations, medical residents can hone their diagnostic and communication skills before they face similar scenarios with actual patients. The drama students benefit as well.

“I’ve wanted to act for a while, and I’ve always been interested in medicine, so this was a perfect combination,” says UW creative writing major and drama minor Lev Parker, who played the role of the patient on the gurney. “This was my first performance, my first stage.”

The Value of Simulations

Simulations are not new in health care — the UW has a “standardized patient” program involving simulations for clinical training — but neurology training has traditionally been “lecture-based with a lot of self study,” explains Wolfgang Muhlhofer, associate professor and vice chair of education in the UW Department of Neurology. “That’s not really putting our trainees’ active problem-solving, medical decision-making, and communication skills to work.”

Simulations are really important because they rehearse for real life. ...They allow us to engage and activate our whole bodies, our emotions, to gain knowledge and skills.

To address this, Neurology introduced a full-day “bootcamp” of simulation training for incoming residents in 2022. For the role of patients, Muhlhofer looked into using paid “standardized patients” through the UW's standardized patient program, but the cost and lack of availability on the date of the planned bootcamp were barriers. So he reached out to School of Drama faculty about recruiting student actors as volunteers.

Initially, Drama faculty felt uncomfortable asking students to take on an acting job without payment. Then Scott Magelssen, professor of theater history and performance studies, offered to create a two-credit course for those interested in participating. Having spent his career studying simulations in various contexts — from living history museums to simulations preparing soldiers for combat — Magelssen knew how valuable simulations can be.

“Simulations are really important because they rehearse for real life,” Magelssen says. “They use the tools from theater and performance to create a world that is realistic enough that the training feels authentic. They allow us to engage and activate our whole bodies, our emotions, to gain knowledge and skills.”

Drama students signed up for Magelssen’s course and participated in the neurology boot-camp simulations. The simulations were so well received by neurology residents that Neurology began offering optional two-hour simulation workshops each quarter. Drama students have continued to be involved.

“I think our drama students are hungry for these kinds of experiences,” Magelssen says. “This was a way to have them participate in the simulations but also have an educational component, an opportunity to reflect on the ways they are using their skills and how their art can make an impact in the world outside of the theater.”

Preparing for the Unexpected

Like any acting role, the simulation actors arrive prepared, with guidance from Muhlhofer. He first sends an email describing upcoming simulation scenarios, then discusses the scenarios in more detail with interested students over Zoom. Before the event, the students get a script — “more like Cliff Notes,” Muhlhofer says — with information about their character and the story to tell the trainee physicians. The notes include things they should mention to the trainees, as well as things they shouldn’t volunteer and subtext for the character.

“Subtext is important because patients don’t just show up with a symptom,” says Muhlhofer. “They all have a story that they carry around with them. A lot of times I leave it up to the actors to improvise based on some basic personality traits, some basic emotions they should have in this particular situation.”

Muhlhofer meets with the actors in person for a dry run before the simulation event. He plays the role of the trainee physician and provides suggestions for making the patient’s physical symptoms and emotional responses as believable as possible. The more real the scenario feels, the more the neurology residents will learn from it, he explains.

Sometimes Muhlhofer is surprised at how intense the experience can be for the residents. He recalls one scenario in which the patient complained of a headache and suddenly became unresponsive and had a seizure. “The calm scenario turned into this really high stress situation,” says Muhlhofer. “The resident was rushing around the bed, trying to interact with the patient. The resident’s pager fell to the ground, so the resident kicked it across the room to get it out of the way while yelling orders to the nurse. They had a visceral response to what was happening and got so into it that it felt real.”

Not all simulations are that dramatic, but there are always surprises — even for the actors. Colleen Carey, a comparative history of ideas major and drama minor, recalls playing the role of a patient admitted to the emergency room with a cluster of symptoms. The simulation was run twice with different trainees. Both sought the patient’s consent for immediate intubation, but one was somewhat brusque in delivering this difficult news while the other was skilled and empathetic. Each elicited a different response from Carey.

“Both simulations were not at all what I expected, and yet both offered surprising gifts about the art of medicine as well as the art of communication,” Carey says.

Though the simulations are designed for training neurologists, they also strengthen the drama students’ skills in building a character and improvising under pressure. “In their reflective essays, a lot of our students talk about how this experience helped them build their confidence as a performer,” Magelssen says. “Asked if they would recommend this experience to others, across the board they say ‘yes.’”

Some students, like Carey, have participated many times. With each simulation, she gains something new.

“I continue to find such profound purpose in this work,” Carey says. “There are lessons I continue to learn in this arena that cannot be learned anywhere else.”

Interested in participating in Department of Neurology simulations during the next academic year? Email Wolfgang Muhlhofer (Department of Neurology) at wmuhlho@uw.edu or Scott Magelssen (School of Drama) at mmagelss@uw.edu to learn more.

More Stories

A Healing Heart Returns

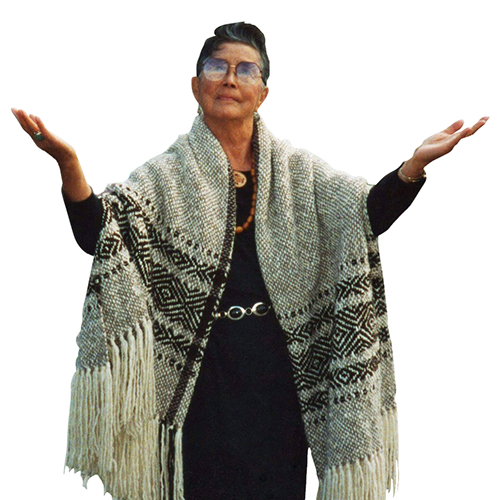

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.

A Transformative Gift for Arts & Sciences

To honor his wife and support the college that has meant so much to both of them, former Arts & Sciences dean John Simpson created the Katherine and John Simpson Endowed Deanship.

Can Machines Learn Morality?

UW researchers at the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences and in the Allen School are exploring the potential for training AI to value altruism.