“What is a bow made of?” “How does it make sound?” “How long did it take to learn to play cello?”

The questions came fast and furious when students at T.T. Minor Elementary School met with members of the Marian Anderson String Quartet in November. The quartet visited the school several times during a week-long residency in Seattle that culminated in a concert presented by the UW World Series at Meany Hall for the Performing Arts.

The UW World Series, which presents internationally acclaimed artists in music, theater, and dance, sponsored the quartet’s residency and is planning dozens of others this year. Some residencies include school or community visits, with support from the Ladies Musical Club; others focus on master classes for UW students. All include a performance at Meany Hall through the UW World Series.

“Four years ago, education was ancillary to our mission,” says Matthew Krashan, director of the UW World Series. “Now it is a core part of our mission. Both children and adults need exposure to the arts, and we feel that our educational programs provide opportunities that are vitally important in today’s world.”

The numbers support Krashan’s claim. Two years ago, UW World Series funded 19 residencies; last year the number more than doubled. This year there will be close to 60 residencies scheduled. “Now when we are considering booking an artist, one of our first questions is, ‘Would you be interested in doing a residency?’” says Krashan.

For the Marian Anderson String Quartet, the answer was easy. The quartet—the first African American ensemble to win a major classical music competition—considers residencies an essential part of its work and does them often. “We’re not ‘here one day and gone the next,’” says Marianne Henry, violinist and a founding member of the quartet. “It’s important for us to come in and get into the community before having a concert.” During their week in Seattle, they visited four schools and two churches before performing at Meany Hall.

It helps that each quartet member recalls being inspired by a musician early in life. “I remember musicians coming to my third grade classroom,” says Henry. “I immediately fell in love with the sound of the violin and have played ever since.” Violist Diedra Lawrence had a similar experience when a violinist performed at her high school. “I was stunned by what I saw—to be that close to it,” she says.

Henry admits that interacting with audiences, rather than just performing, takes some getting used to. “It definitely takes practice,” she says. “You have to practice speaking to an audience and

then sitting down and turning it off to play well. On another level, it makes me feel good. I like connecting with an audience before I play.”

Young audiences are particularly challenging—and satisfying—since many students are hearing classical music for the first time. “We start by introducing the instruments individually, and then talk about how the quartet is set up,” says violinist Nicole Cherry. “If the students are young, we play a game where they close their eyes and figure out which instrument is not playing. We also talk about dynamics, such as the loudness or softness of tones. The visit usually ends with a question and answer session.”

School visits are powerful but limited in their reach. To introduce even more students to music, the UW World Series also offers free student matinees at Meany Theatre, with classes arriving by school bus to attend. Teachers receive study guides prior to the event to help prepare their class. “We keep the information simple,” says Jan Steadman, market-ing and public relations director for the UW World Series. “It’s simple enough that the teachers actually have time to use it.”

The matinees, designed specifically for younger audiences, include excerpts from the regular performance. “We work with performers ahead of time to be sure the material is appropriate, both in content and age level,” says Alice de Anguera, educational program coordinator. And if they get it wrong, they’ll know soon enough. “Children know when they’re bored. They know when they’re excited. And they have no qualms about letting you know that,” says Krashan.

As the UW World Series’ outreach to schools has increased, so has its interest in educating adult audiences. It presents occasional forums on arts-related topics, and many of its performances include a 30-minute pre-concert lecture for those interested in learning more. UW faculty

in ethnomusicology and dance serve as lecturers for most world music and dance performances; the Ladies Musical Club provides lecturers for the classical music concerts.

“We started doing the pre-show lectures in earnest about two years ago,” says Krashan. “Now we offer nearly two dozen a year. The audience for them has grown incredibly, with up to 200 people filling the west lobby for the lectures. It’s that desire to learn more and get more out of the performance.”

UW students are also benefiting from the UW World Series’ educational focus. Every time a residency is planned, the performers are encouraged to teach a master class for UW students. In music, this means observing as UW students perform a piece of music, then providing comments on the students’ interpretation or technique. In dance, the visiting dancers teach one or more classes that introduce their particular technique.

“Master classes can be an important part of understanding dance history,” says Kelly Knox, a student in the Dance Program’s M.F.A. program. “A dance company’s technique cannot be passed on through literature. It has to be passed on from dancer to dancer.”

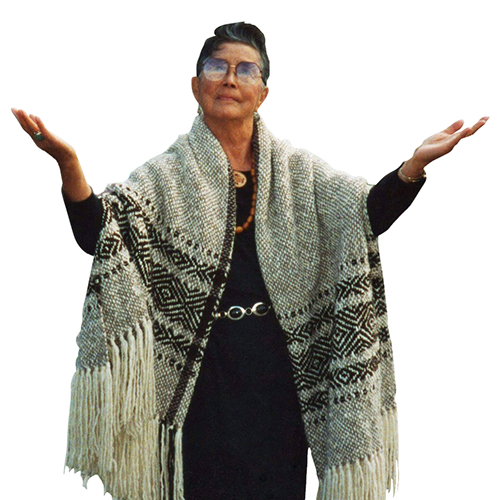

For its residency in January, members of the Limón Dance Company taught seven master classes, sharing their technique with beginning and advanced students. The challenge, they say, is to make a meaningful connection in one or two class sessions. “For one class, we had just 90 minutes,” says Limón dancer Roxanne D’Orleáns Juste. “In that situation, I take a look at the students and quickly make an assessment, watching their body language. Then it starts, like any dialog. It’s important to keep it simple, but challenging.”

Adds artistic director Carla Maxwell, “No one is going to get a profound understanding of the work in one class, but hopefully something will touch them. It doesn’t matter if these students go on to become dancers. If it is a valuable experience for them, then they will take that and channel it in some way.”

The same can be said of all educational offerings sponsored by UW World Series. If they encourage an appreciation for the arts, if they open some eyes to the possibilities of expression through music and movement, they will have succeeded.

“For the performing arts to stay vital, we need to inform and develop new audiences,” says Krashan. “I also believe the arts provide a kinder, gentler perspective on the world that children need. The UW World Series is dedicated to helping with this effort. It’s something that is very important to us.”

More Stories

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.

A Healing Heart Returns

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.

Need a break from holiday movies? Try these

For those wanting a break from holiday movies, Cinema & Media Studies faculty and grad students offer suggestions.