Even the most advanced aircraft can’t fly as skillfully as a housefly.

That’s why researchers at the UW’s Air Force Center of Excellence on Nature-Inspired Flight Technologies and Ideas are studying how insects move, navigate, and use their senses during flight. The Center, housed in the Department of Biology in partnership with the College of Engineering, is one of six nationwide centers funded by the U.S. Air Force. It is the only one to focus on how elements in nature can help solve challenging engineering and technological problems related to building small, remotely operated aircraft.

“Our goal is to reverse-engineer how natural systems accomplish challenging tasks,” says center director Tom Daniel, a UW biology professor who holds the Joan and Richard Komen Endowed University Chair. On a PBS Newshour segment, while prepping a moth for a flight experiment, Daniels explains, “What we’re really interested in doing is asking, ‘How does [the moth] process information and accomplish tight maneuvers in a complex habitat?’ With a tiny brain, they’re accomplishing maneuvers that we can’t get any aircraft to do.”

Working with partners at other universities in the U.S. and Europe, researchers at the center will focus on three main research areas: how animals locate objects by encoding and processing information through their senses; how they navigate in complex environments and skillfully avoid collisions; and how they navigate in sensory-deprived environments, such as flying in low light or where their ability to smell and hear might be compromised.

Learning from the behavior of insects and animals could inspire more advanced micro-air vehicles, or small, flying robots. These could be used in difficult search-and-rescue missions, or to help detect explosives or mines when it would be too dangerous for humans to go on foot or in vehicles.

“Small autonomous unmanned vehicles have the ability to move into spaces and search for injured people or assess structural health in situations where human emergency responders simply cannot access in a safe way, such as in the Oso, Washington, mudslide or the Fukushima plant after the 2011 tsunami in Japan,” said Kristi Morgansen, a UW associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics and one of the center’s faculty leads.

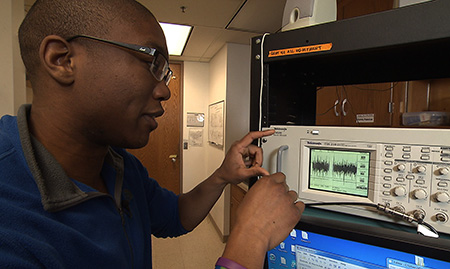

Researchers at the UW will work in the center’s core lab in Kincaid Hall, where a large animal wind tunnel allows them to test how animals fly and process sensory information. The team hopes to build an additional motion-capture system to study animal flight and even quadrotors, small helicopters that could become “smarter” flyers by using the sensing abilities of animals.

Aside from these applications, center researchers will also develop micro-air vehicles for environmental monitoring. A micro-scaled quadrotor could, for example, navigate through a thick forest to the tree canopy and measure temperature, moisture and gases at different levels in the atmosphere. Or, small unmanned aircraft could be used to track ocean mammals such as whales for more consistent monitoring.

Funding for the new center comes from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, which will award up to $9 million spread over six years, provided the center passes a renewal every two years. The Department of Biology, the Department of Applied Mathematics, the College of Arts & Sciences, the College of Engineering and the Office of the Provost also are providing money for the center.

For the Air Force, the funding is part of an investment in basic research with universities and industry laboratories to help transition research results to support the Air Force’s needs, without specific applications or products in mind.

“That being said, it is possible that this information could be used for enabling more efficient aircraft flight, better control of remotely piloted vehicles, or even better capabilities for rescue operations,” says Patrick Bradshaw, program officer with the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. “Being able to understand and mimic nature may enable us to do many other things we don’t even realize we can do yet.”

For more information, visit the Nature-Inspired Flight Technologies + Ideas (NIFTI) website.

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.