Imagine buying your dream home — and then learning you are prohibited from owning it. A surprising number of residential property deeds in Washington state contain clauses excluding certain groups from ownership.

Those clauses are no longer enforceable thanks to a 1968 anti-discrimination law, but the exclusionary language — a reminder of sanctioned racism in the past — can nevertheless be disturbing for homeowners.

“When homeowners learn about a restriction it can be quite a shock, especially for families of color,” says James Gregory, Williams Endowed Professor in the Department of History. “Real estate companies have seen some potential buyers walk away from properties out of shock and disgust.”

Earlier this year, the Washington State Legislature passed HB 1335, which funds research at the University of Washington and Eastern Washington University to search for racially restrictive covenants in home deeds. When the researchers find such covenants, they will inform the homeowners and suggest measures to repudiate the disturbing language.

A History of Segregation

For Gregory, who leads the UW research team, the current work is a continuation of a research project started years ago with the help of students in his classes. The earlier findings are published on Gregory’s Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project website. With state funding now attached to the project, he sees an opportunity to bring greater visibility to Washington’s complicated relationship to segregation.

“As a historian, I think it’s important to fully understand the history of segregation in our region, which continues to haunt the systems of opportunity that differentiate folks who have faced discrimination from those who have not.” says Gregory. “To forget or hide or not understand that history is to really limit our ability to be responsible to that.”

Racial segregation has long been a part of Seattle’s history. Early on, the city passed a law prohibiting Indigenous Americans from staying in the city at night. In the 1880s, Chinese people were forced to live in a very contained Chinatown. The practice of putting deed restrictions into property records became popular in the 1920s, after attempts to create segregated zones in cities were deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

As a historian, I think it’s important to fully understand the history of segregation in our region.... To forget or hide or not understand that history is to really limit our ability to be responsible to that.

“After that 1917 Supreme Court ruling, realtors, developers, cities, and counties started using a workaround — putting restrictions in deeds and property records rather than zoning,” says Gregory. “Typically a developer of a new subdivision would write the restriction into the original plat or document for the whole subdivision.”

In 1926, the Supreme Court ruled that such documents were legal and enforceable in court, which popularized the approach in Washington state and across the US. The practice continued for three decades, finally waning in the 1950s with the growth of the civil rights movement.

A Painstaking Process

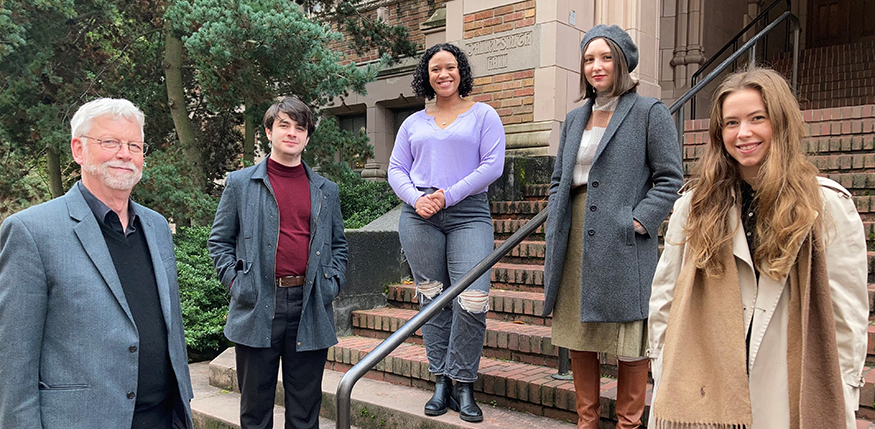

Thanks to state funding, Gregory now leads a team of four students searching for deeds with exclusionary language. Project coordinator Madison Heslop, a doctoral student in the Department of History, is joined by history majors Jazzlynn Woods and Sophia Dowling and computer science major Nicholas Boren.

Reviewing the language in thousands of home deeds is a painstaking process. “The work can be really tedious at times, but I think it’s really important,” admits Woods, who has been surprised by the frequency with which she has encountered racially restrictive covenants. “When it becomes tedious, I just keep in mind that in the end it will be really useful, informative, and liberating for people.”

The researchers mostly look for certain words or phrases — whites only, Caucasians only — that appear frequently in restrictive covenants. But the documents often get more specific. Sometimes unusual wording appears, such as “Ethiopian” for anyone of Sub-Saharan African descent or “Asiatic” for anyone of Asian descent. After Filipino homebuyers argued they were not “Asiatic” and should be welcome in restricted neighborhoods, the term “Malay” began to appear to exclude them. “Hawaiians” were sometimes mentioned as well.

For historians, these wording choices provide insights into the past — and offer some surprises. Gregory recalls a 1948 covenant from Bellevue-adjacent Clyde Hill that states "Aryans only." The dates on that were shocking to Gregory. “The founding director of the Bellevue Chamber of Commerce was putting those restrictions on property when Hitler had been dead for three years," he says. "The Holocaust and the whole concept of Aryan supremacy was well known by then, yet he still chose that wording. That was so disturbing.”

Repudiating Restrictive Language

That Clyde Hill covenant was sent to Gregory by the homeowner, but the vast majority of restrictive covenants are identified by student researchers reviewing county government records. Some deeds are on microfilm at the King County Archive; others — records from 1890 through 1930 — have been digitized. Computer science major Boren has created a program to make the digitized documents machine readable and searchable by key words, which will speed the discovery process considerably.

Beyond King County records, the UW team is reviewing property records from Snohomish and Pierce counties. Additional student researchers will be hired to focus on other Western Washington counties.

Next year, in the second year of the project, property owners with racially restrictive covenants will be notified. While disturbing language cannot be eliminated from property records, the law enables homeowners to repudiate the language by filing a “restrictive covenants modification form.” With this new knowledge, it will also be more difficult for home sellers to plead ignorance on disclosure forms.

“I think this will prompt people, at least at the time of a home sale, to file the modifications form — and real estate companies will help sellers do this,” says Gregory.

Woods hopes this project will help people recognize that liberal cities like Seattle have not been immune from segregation, discrimination, and unequal treatment.

“These practices have deprived people of color, especially Black people, of generational wealth and homeownership,” Woods says. Looking ahead, she hopes for “some kind of action by the legislature, the county, or the City of Seattle to work towards atoning for these wrongs — and maybe even some form of reparations.”

Learn more about restrictive covenants and their history on the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project website.

More Stories

Exploring the World — and Global Careers

Study abroad in Vietnam and Madrid. An internship with the State Department. International studies major Grace Kelly explored the world as a UW student.

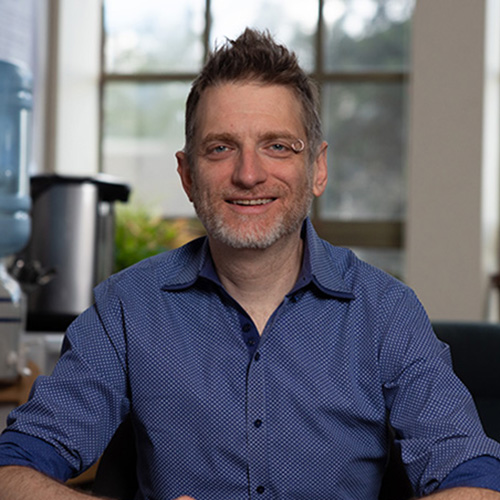

The Challenge of Peer-Produced Websites

Communication professor Benjamin Mako Hill studies why successful peer-produced websites (like Wikipedia) eventually struggle to maintain their openness to new contributors.

Advocating for Better Health Care

As director of government relations for the Catholic Health Association, Paulo G. Pontemayor (BA, 2005) is dedicated to increasing equity and access to health care in the United States.