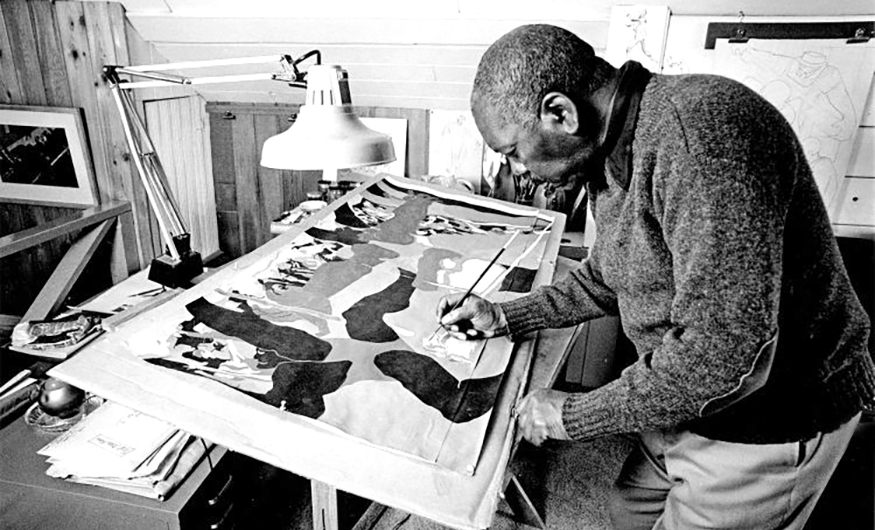

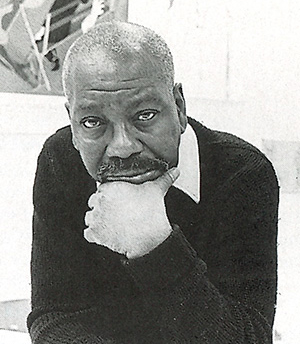

Jacob Lawrence was a renowned artist when he joined the faculty of the UW School of Art in 1971, at age 54. The new role meant leaving New York City, one of the largest communities of Black artists in the US, to move to Seattle with his wife, artist Gwendolyn Knight. The couple assumed they would eventually return to New York. Instead, Seattle became their permanent home.

Lawrence had a profound impact on students at the University of Washington — where he taught until 1986 — and on the broader arts community in the Pacific Northwest. Recognizing his impact, School of Art faculty chose to name the Art Building’s first floor gallery in honor of Lawrence in 1993.

Naming a gallery is one thing. Having the gallery live up to that name, they discovered, is quite another.

“The gallery got off to a good start when it was founded, but a lack of resources and vision limited its presence on campus,” says Jamie Walker, director of the School of Art + Art History + Design (SoA+AH+D). “When I was appointed director of the School in 2014, the gallery was already one of my priorities. With encouragement from faculty, students, and several people in the Black arts community, we rededicated our efforts to make the gallery a place that would honor and respect the legacy of Jacob Lawrence.”

The Jacob Lawrence Gallery has since been revitalized, with the addition of a professional gallery director and curator and the creation of special programs reflecting Lawrence’s legacy. This spring, another improvement will be realized as the gallery moves into a new home through a renovation of the UW Art and Music Buildings.

Sharing History Through Art

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the gallery’s namesake, Jacob Lawrence, in the artworld. Lawrence first earned national recognition at age 24 when he created The Migration Series, a collection of 60 paintings depicting the “Great Migration” of African Americans from the South to North at the beginning of World War I. He went on to create other historical series and received numerous honors, including the prestigious National Medal of Arts in 1990. He died in June 2000.

“Lawrence used art to tell complex stories about Black life, which I think is such a generous opening gesture: ‘look at what we've done,’” says Kemi Adeyemi, UW associate professor of gender, women and sexuality studies and director of The Black Embodiments Studio (BES), an arts writing incubator and public programming initiative dedicated to building discourse around contemporary Black art. “I think Lawrence’s approach to storytelling crosses time and space and has allowed generations of people to connect to and through his work.”

In a Provost’s Town Hall presentation about Lawrence in 2021, art historian Juliet Sperling noted that the artist worked in dialogue with a long American tradition of history painting that had been out of style for nearly a century. “Through deeply researched projects like the Migration Series of 1940-41, he resurrected the genre and stripped away the sap, exposing the raw story at the core,” noted Sperling, UW assistant professor of art history and Kollar Endowed Chair in American Art. “His art reminds us that the way we tell history matters; he challenges us to revisit familiar stories through different sets of eyes.”

Honoring Lawrence's Legacy

When Walker became director of the SoA+AH+D, his first priority for revitalizing the Jacob Lawrence Gallery was to hire a professional gallery director. The budget was meager, which might explain why previous gallery managers ranged from graduate students to a woodshop technician. But by dedicating additional SoA+AH+D funds, plus a stipend from the Arts & Sciences Dean’s Office, the School was able to hire Scott Lawrimore, previously the head curator for the Frye Art Museum.

I think Lawrence’s approach to storytelling crosses time and space and has allowed generations of people to connect to and through his work.

Lawrimore clarified the gallery’s mission — to develop exhibitions and programming around the notion of social justice and the legacy of Jacob Lawrence. He then curated thematic shows and created the Jacob Lawrence Legacy Residency, an annual month-long residency for a Black artist with an interest in social justice. The artist spends January at the UW creating work, which is exhibited in the gallery in February, Black History Month.

Steffani Jemison arrived in Seattle as the 2016 artist-in-residence soon after having a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that paired her work with Jacob Lawrence paintings. When Walker asked her why she chose to participate in the UW residency, she explained that it was a huge honor to be in Jacob Lawrence’s gallery. “She said, ‘I wouldn’t be here without Jacob Lawrence,’” Walker recalls. “Just about every resident we’ve had, it’s been the same reason. They all said that Jacob Lawrence’s focus on social justice and racial equality throughout his career inspired them and their work.”

After three years as gallery director, Lawrimore passed the baton to Emily Zimmerman, who expanded the ambitious programming and outreach of the gallery, including the creation of MONDAY, a publication of critical art writing. But both directors were stymied by physical limitations of the gallery, most notably its lack of a security system and climate control, which meant that museums would not lend work to the gallery. Fortunately, those issues will soon be a thing of the past thanks to the gallery renovation.

A Welcome Renovation

The Provost’s Office and the Arts & Sciences Dean’s Office together covered two-thirds of the renovation expenses, with private support from SoA+AH+D donors covering the final third. The architecture firm Mithun, recently named firm of the year by the American Institute of Architects, was hired in 2021.

The gallery’s new location will be just feet away from a building entrance off the Art Building courtyard. Exterior windows designed by Kristine Matthews, SoA+AH+D associate professor of visual communication design (VCD), and VCD alumna Edith Freeman (BDes, 2022), will catch the attention of passersby. Best of all, the gallery’s security and climate control systems will now meet American Alliance of Museums standards, so works from other galleries and museums can be loaned to the Jacob Lawrence Gallery.

Adeyemi has worked closely with the Jacob Lawrence Gallery through the Black Embodiments Studio and looks forward to the possibilities of the new space. “I'm always interested in how we can use the art gallery as a space to be in conversation with art, to not just think of the gallery or the museum as sites where we passively consume art,” Adeyemi says. “The plans for the new gallery space have been developed with an eye toward breaking down the kinds of alienation people can feel when it comes to the arts, so I'm really looking forward to the kinds of programming that BES can bring to the new gallery space.”

With the gallery displacing other Art Building spaces, the renovation has led to other Art Building improvements as well. A new woodshop will finally have a proper dust collection system, and a new glass lampworking studio will have proper ventilation. There will be a new Advanced Concepts Lab with 3D printers, laser cutters, and other equipment, and a new introductory ceramics studio. A welcome gathering space has been added at the gallery entrance.

Zimmerman left her role as gallery director at the start of the renovation; Walker is hoping to have someone new in the role before summer. A 50% curatorial fellowship position has been added to support the director. The future for the Jacob Lawrence Gallery is bright, and worthy of its namesake, who has meant so much to so many.

“I didn't know Lawrence personally, but I think his approach to thinking about art as a practice of community resonates with the next steps of the gallery space,” says Adeyemi. “I think we will find more and more ways to invite students in, from across campus, and to make them feel that sense of comfort and community that can be built when we gather around art.”

More Stories

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.

A Healing Heart Returns

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.

Need a break from holiday movies? Try these

For those wanting a break from holiday movies, Cinema & Media Studies faculty and grad students offer suggestions.