Voting in most American elections is simple: select one preferred candidate for each position and submit your ballot. But is that the best approach?

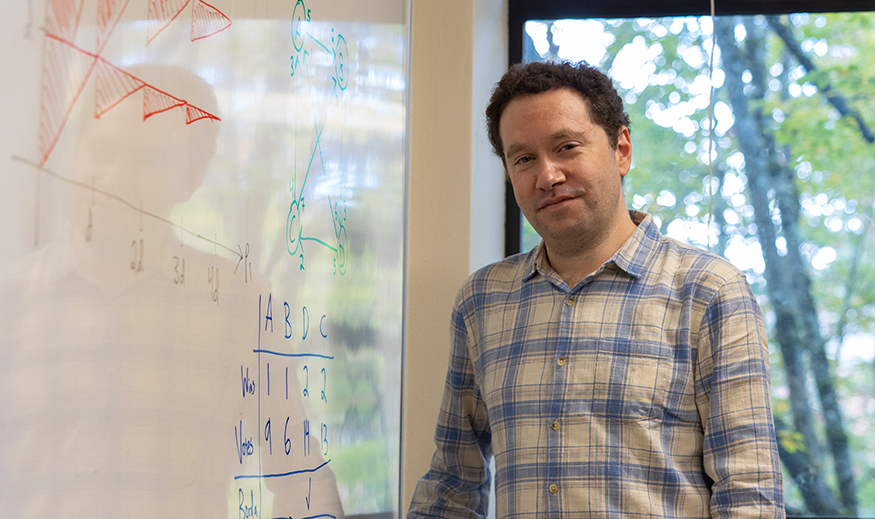

That question intrigues Jonah Ostroff, associate teaching professor in the Department of Mathematics. Ostroff is currently teaching an undergraduate course, Mathematics & Democracy, that explores the mathematics behind voting systems and other political processes. He designed the course to be accessible to all UW students regardless of major.

Students in the course quickly discover that every voting system has benefits and pitfalls. “One thing that comes up a lot is that you cannot achieve all the things you want in one voting system,” says Ostroff. “There are certain ways that we measure fairness, and we might want all of them to happen, but mathematically that is impossible. We have to decide which properties to prioritize.”

No Perfect Voting System

Ostroff explains that the main goal of any voting system is to accurately reflect the will of voters. But making the voting process easy is also important. “Voters shouldn’t need to strategize,” says Ostroff. “They shouldn’t need to question whether they are wasting their vote. You want to take the strategic weight off their shoulders and just have them share what they think.”

The most common voting system in the US — known as “plurality” or “first past the post” — is particularly simple to navigate. Voters simply choose one candidate for each position. In races with two candidates, that system works well. But when a race has multiple candidates, things get more complicated. Voters must decide whether to choose their favorite candidate or the person they think has the best chance. In such situations, ranked voting may be preferable.

“Ranked voting” is an umbrella term for a range of voting systems that allow voters to rank multiple candidates in a race. “We talk about five or six common examples of ranked voting systems in class,” Ostroff says, “but with all the little tweaks people have made, I’d say there are dozens.”

In one popular ranked voting system, the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated and those who voted for that person have their votes passed to their next favorite candidate. The process continues until a final outcome is reached. That approach can work well but can sometimes lead to counterintuitive outcomes — such as the possibility for voters to accidentally hurt a candidate’s chances by voting for them. (See sidebar for example.)

Another voting system Ostroff covers in class is approval voting, which has voters assign a “yes” to as many candidates as they like and ignore the rest. “It’s a simpler system than ranking all the candidates,” Ostroff says. “Maybe there’s only one candidate you want to give your vote to, or you actually like half the candidates and want to give all of them your vote. This method does satisfy most of the criteria that we want in a voting system.”

There are certain ways that we measure fairness, and we might want all of them to happen, but mathematically that is impossible. We have to decide which things to prioritize.

Where approval voting falls short is when the goal is to elect multiple people, such as several members of a city council. “It’s not good at getting diverse representation in that situation, because if a slim majority prefers a set of candidates, they will get all of those candidates,” Ostroff says. “But for electing a single person, it’s great.”

So why is plurality still the most common voting system in the US?

“Inertia,” says Ostroff. “Changing systems requires explaining to voters why a more complicated system is better, and that’s not an easy explanation. And while there might be compelling reasons to switch, every system has its advantages and disadvantages, so it’s never really a slam dunk.”

Yet change is possible. Thanks to a ballot initiative passed in 2022, the City of Seattle will have ranked-choice elections beginning in 2027, joining many other cities across the country. Maine was the first state to use ranked choice in federal elections, beginning with their congressional elections in 2018.

A Question of Representation

Elections are just one mathematical question covered in class. Another is apportionment — how the number of Congressional representatives for each state is determined (which also determines the number of Electoral College votes for each state).

Ostroff is fascinated by the political wrangling that apportionment inspired among the founding fathers. They agreed that the number of state representatives should be proportional to the population of each state, but they disagreed about how to calculate that. Alexander Hamilton proposed an apportionment method that seemed most intuitive, but Thomas Jefferson proposed a different approach that benefited large states like Virginia. He and James Madison convinced George Washington to veto Hamilton’s bill — the first veto in American history — and the more mathematically cumbersome system proposed by Jefferson was adopted.

Over the next century, the apportionment system changed several times, but it was not until the 1920s that the current system was developed by Harvard mathematician Edward Huntington and Joseph Hill, chief of the Census Bureau at that time. Their system was implemented in the 1930s and enshrined into law in the 1940s.

“There were 435 representatives at that point,” says Ostroff. “The government passed a bill to adopt the new system and keep the same number of representatives forever. That’s why the number of representatives is still 435 nearly a century later, despite our population increases.” The result has been a rounding of the number of representatives that benefits smaller states, which is why a representative in Wyoming now represents many fewer people than one in California. “This is something we could theoretically change, but it hasn’t really been touched in the last hundred years,” says Ostroff.

Along with apportionment, Ostroff touches on gerrymandering and other math-related topics in his course. He would love to explore those topics in more depth, but there’s only so much he can cover in one quarter. What’s most important, he says, is to show how mathematics plays a role in all our lives.

“I want the students to see that math is more than what they’ve seen in calculus,” Ostroff says. “There are all sorts of interesting questions that you can approach from a mathematical perspective. And I want them to see that the math itself is fun.”

To learn more about various voting systems, Jonah Ostroff suggests the book “Mathematics and Politics: Strategy, Voting, Power, and Proof” by Alan D. Taylor and Allison M. Pacelli.

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Sports Obsession Inspires a Career

Thuc Nhi Nguyen got her start the UW Daily. Now she's a sports reporter for Los Angeles Times, writing about the Lakers and the Olympics.

Through Soil Science, an Adventure in Kyrgyzstan

Chemistry PhD alum Jonathan Cox spent most of 2025 in Kyrgyzstan, helping farmers improve their soil—and their crops—through soil testing.