You’ve just thought of something you don’t want to forget. Your instinct is to grab a pen or your cellphone and jot a note. For most of us, written language is second nature. But the invention of written language — the idea of creating a permanent visual record that accurately represents thought or speech — was a huge leap in human civilization.

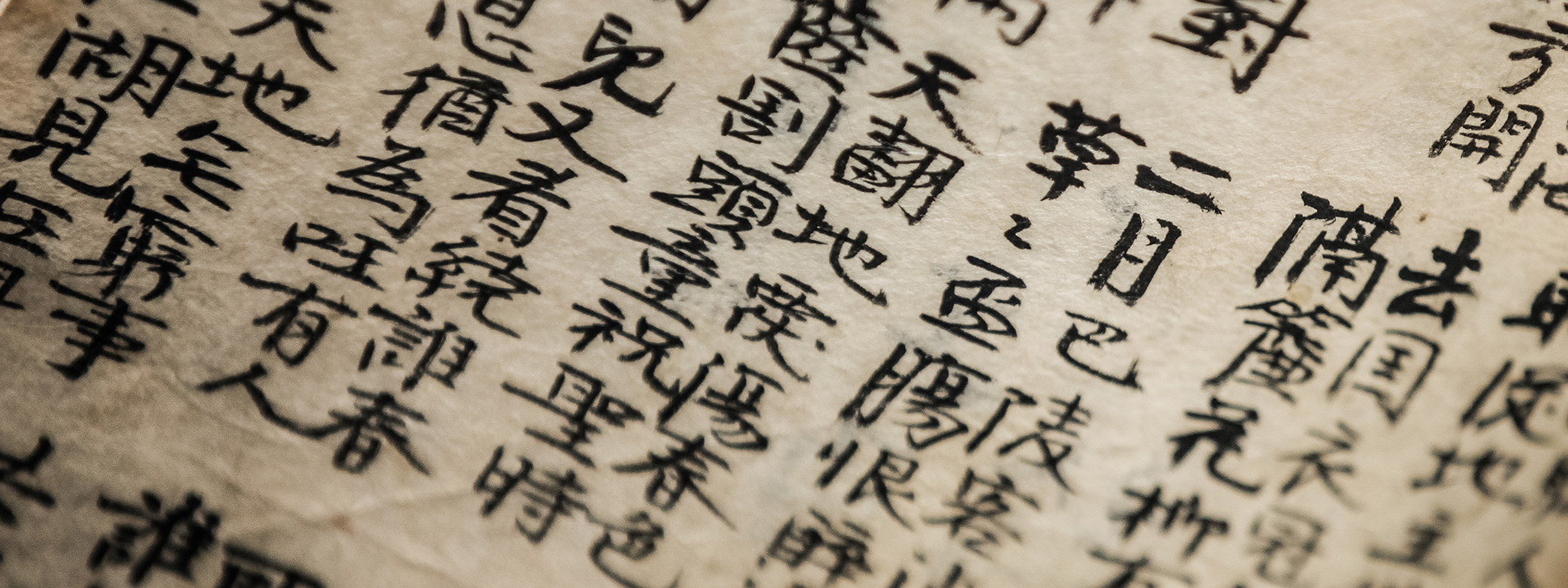

Based on the archaeological record, that leap has happened independently in just a handful of ancient civilizations. Sumerian cuneiform was invented around 3500 BCE, followed by Egyptian hieroglyphs. Chinese characters appeared about 2,000 years later. Mesoamerican writing came much later but is also believed to be an independent invention.

Of these four writing systems, only Chinese characters are still in use. From China, the writing system spread across East Asia to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan, and is still used in China and Japan in a modernized form.

In his book Chinese Characters Across Asia, Zev Handel, professor of Chinese in the Department of Asian Languages and Literature, explores the development of Chinese characters and how they were adapted across East Asia to reflect spoken languages other than Chinese. He also touches on the challenges that the Chinese writing system has faced and — so far — survived.

“Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian cuneiform each lasted about 3,000 years, and that’s where we are right now with Chinese,” says Handel. “Will Chinese characters last another 3,000 years, or another century? It’s hard to know.”

Adapting a Writing System

To understand the spread of Chinese characters as a writing system, it helps to understand how characters function. They are not pictographs that literally represent things, though like all primordial writing systems, they started that way.

“The secret to kick-starting a writing system is the realization that you can use a drawing of something not to represent that thing, but represent the word for that thing,” says Handel. “It’s a very simple idea, but it’s not at all obvious until it happens. But our languages are so complex that most words are not amenable to drawing, so you need a way to take that beginning, the few hundred pictures that have now turned into writing, and develop that further so you can precisely record any sentence made up of any sequence of words. And to do that, you have to repurpose some of those pictures.”

One approach, Handel says, is to separate the semantic and phonetic aspects of a picture, borrowing either its meaning or pronunciation for other uses. For example, using phonetics, an illustration of an eye could represent the word “I,” a bee could represent “be,” or a knot could represent “not.” Such repurposing allows the expansion of the writing system. Before long, the writing is stylized and simplified, and the original pictures are no longer necessary. That’s how the written form of Classical Chinese developed.

The Chinese writing system spread to Korea and Vietnam about 2,000 years ago, and to Japan more than 1,000 years ago, as China dominated the region. Official business in those countries was conducted in Classical Chinese regardless of each country’s own spoken language. Eventually, people literate in Classical Chinese began adapting the characters to create a written form of their own language.

Handel explains how that might happen, using an imagined scenario of an English language speaker in need of a written language. After learning the Chinese character for "fish," 鱼, they might decide to write the English word "fish" using that same character. Or instead, they might use the pronunciation of the character for fish—"yú" in Mandarin—to write the similar-sounding word "you" in English. Using either the sound or the meaning of a character, they could connect it to something in English, and when necessary, modify the character to indicate whether its use was phonetic or semantic.

“They’d be using the same basic form of characters as used to write Classical Chinese, making it work for how their own language sounds,” says Handel. “This new written language would superficially look like a string of Chinese characters, but it would be nonsensical if you tried to read it aloud as Chinese. In the same way, a Latin speaker from 2,000 years ago would recognize the Latin alphabet used to write modern English, but if they tried to read a sentence, it would be gobbledygook to them.”

A Sudden Shift

Korea and Vietnam used Chinese characters to write their own languages for two millennia. Japan adopted Chinese characters for its language around the 6th century CE. But it took just a few decades in the early 20th century for everything to change. As nationalism swept the globe, countries around the world jettisoned writing systems that reflected an imperial system of the past.

Korea and Vietnam abandoned Chinese script, replacing it with alphabetic writing systems specific to their own languages. Japan continued to use Chinese characters, but the characters were modified to reflect modern Japanese speech. Even China abandoned Classical Chinese — an outdated classical language that no one actually speaks — for modern standard Chinese writing, which uses simplified characters and standardized grammar to reflect spoken Mandarin.

Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian cuneiform each lasted about 3,000 years, and that’s where we are right now with Chinese. Will Chinese characters last another 3,000 years, or another century? It’s hard to know.

Though Chinese characters have been modified, the writing system survived that transition. But other challenges have emerged. Many technological advancements introduced by the West--the telegraph, the typewriter, the computer, the internet—were designed with Western writing systems in mind and required adaptions to accommodate Chinese and Japanese writing.

“With each new technology, people said, ‘We need to get rid of Chinese characters or we can’t keep up,” Handel says. “And every time, the technology then advanced to the point where it became pretty easy to accommodate Chinese characters. Now things have stabilized. There’s voice recognition and auto completion. You can type in Chinese or enter text in Chinese using voice recognition relatively easily. So, I think technology is not a threat anymore.”

Handel adds that the very quality of Chinese characters that has made them a challenge for Western technology is also what makes them special.

“In a sense, Chinese characters are just like any other kind of writing—a way to preserve speech by putting it into a visual form,” Handel says. “But because characters write meaningful elements of language, not just sounds, they have this capacity to be semantically adapted. And because of that, their spread and adaptation look really different than purely sound-based systems. So while Chinese characters are in some ways very ordinary, they are also special. I'm fascinated by that duality.”

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Love of Classics and Ballroom

Michael Seguin studied Classics at the UW and now owns Baltimore's Mobtown Ballroom. The two interests, he says, are more connected than they might seem.

Need a break from holiday movies? Try these

For those wanting a break from holiday movies, Cinema & Media Studies faculty and grad students offer suggestions.