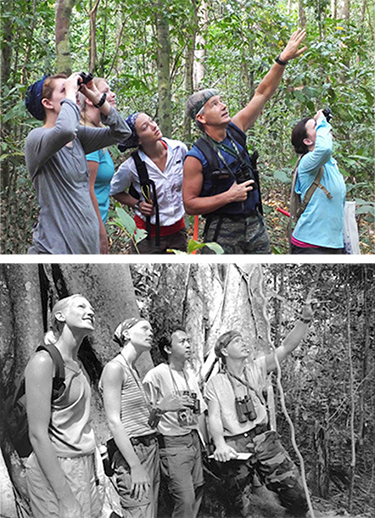

When Matthew Novak set foot on Tinjil Island in Indonesia this summer, it was a homecoming of sorts. Twenty years ago, Novak (BS, PhD, Psychology, 1993, 2002) participated in a month-long field study program on the remote island as a UW graduate student. He returned this year as a professor, along with four of his Central Oregon Community College students.

“I suppose Matt’s students are my grandstudents,” jokes Randy Kyes, research professor in the UW Department of Psychology, core scientist in the UW Primate Center, and director of the UW Center for Global Field Study. Kyes led the field study program when Novak was a graduate student and continues to lead it today. The program focuses on conservation biology and global health, and is open to anyone interested in field research.

Tinjil Island is home to more than 1,500 long-tailed macaque monkeys, as well as monitor lizards and many other tropical fauna and flora. Kyes began leading a summer field training program there for Indonesian students in 1991, through a collaboration between the UW Primate Center and Bogor Agricultural University’s Primate Center. Five years in, he realized that adding UW students would enrich the experience for everyone. “It’s the kind of opportunity I would have liked when I was a student,” he says. He and his Indonesian colleagues offer the program annually, with about six U.S. students and up to a dozen students from Indonesia and other countries participating.

“We’re in a very remote area, in an environment that’s demanding and a bit of a hardship,” says Kyes. “It’s a particular kind of student who wants to venture out and do that for a month, so we’re never looking at huge numbers of students—which is good, because we can’t take that many into a setting like that.”

Novak was in the first UW cohort, in 1995. “I was one of Randy’s guinea pigs to figure out how to get American students to Tinjil,” he recalls. “Now he has a system in place that paces the students through the various challenges of the field study ‘lifestyle.’ It is truly impressive to watch. I am aware of other programs around the world and am fairly certain that Randy has the best program for field study training anywhere in the world.”

For UW participants, most of whom are undergraduates, the program actually begins months before their arrival in Indonesia. They take a preparatory spring quarter course to learn some Indonesian language and develop a proposal for their individual research project. By the time they reach Tinjil, they have a plan for collecting data and are ready to dive in.

Then reality hits.

“I always warn students that nothing will go the way they think it will,” says Kyes. “That’s just the nature of field research. I also tell them not to worry if the research fails. This is about training, about the learning experience, not about doing your final dissertation.” Despite Kyes’s remarks, some students become so committed to their research that they return for a second year to continue it.

The research often requires tromping through dense jungle, using machetes to clear fast-growing foliage. “I had to learn to get past the bugs and the six-foot lizards and keep walking,” Catherine Chu (BS, Psychology, 1999) told Perspectives after participating in the late 1990s. “And I had to learn how to hear and see in the jungle. At first it was difficult to differentiate the noises. There are four birds that sounded like monkeys for the first few days.”

It’s a study abroad where they can study monkeys, but it goes so far beyond that. The cultural interactions are what make it exciting.

In addition to spending hours each day on their research, the students attend daily lectures and take part in field exercises with classmates from Indonesia and other countries. They also take afternoon dips in the Indian Ocean and gather around a bonfire at night, developing international friendships in the process.

“The cultural experience, the opportunity to become global citizens, is a whole other component of this,” says Kyes. “It’s a study abroad where they can study monkeys, but it goes so far beyond that. The cultural interactions are what make it exciting.”

Morgan Wilbanks (BA, Psychology, 2013) spent as much time as possible with Indonesian students and island workers when she participated in 2012. “It was the best way to really experience the culture and learn the most I could about Indonesia and its people,” she says. “I loved it so much that when I returned to Seattle, I dropped my sign language course and enrolled to study Indonesian as my foreign language.” Wilbanks, who had never ventured further than British Columbia before the field study program, has returned to Indonesia since graduating and hopes to pursue a career involving field research and animals.

Not all participants leave the island as enamored. “A lot of people go over there thinking that field research is exotic and exciting,” says Kyes. “They discover that it can be drudgery and boring at times, with a number of hardships. This program can help them decide if field research is something they want to pursue.”

Whatever their decision, alumni’s praise for the field study program has been unanimous. Sharing memories of their experience, alumni repeatedly describe it as “life changing” and “the single most influential experience” during their academic career.

“It was both my first field research project and my first time traveling internationally,” writes one field study alumna who now works for the Washington Department of Ecology. “It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. [At the end of the program,] the last thing Randy said to us was ‘I am very proud of each of you. You are all now real researchers.’ Those words really made an impact on us all.”

For more about the program, visit the UW International Field Study Program webpage.

More Stories

Finding Love at the UW

They met and fell in love as UW students. Here, 10 alumni couples share how they met, their favorite spots on campus, and what the UW still means to them.

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.