This story is the first in a series on Black artists and scholars.

In his 1969 speech, The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity, James Baldwin began with two propositions: the first in which he said, “The poets, by which I mean all artists, are finally the only people who know the truth about us.” He noted in the second that in our present times, it would be awful for a civilization to cease to produce poets or to believe in their observations. To engage art as a poetic involves a willingness to chart unknown courses with grace and patience, trusting the guidance of our inner compass.

Barbara Earl Thomas (BA, Design, 1974; MFA, Painting, 1977) personifies this with a unique ease, made clear by her accomplishments which stem from committing to a disciplined practice of her craft, while trusting in chance, her instincts, and her community. Such a balance is often difficult to attain for many reasons, yet it seems for her a natural embodiment. Thomas, who studied under the direction of world-renowned painters Michael Spafford and Jacob Lawrence, is herself an award-winning artist and writer represented by Claire Oliver Gallery in New York.

Thomas describes herself as a deep-thinking daughter of the American South and the first in her family to be born in Washington state. Her family migrated to the Pacific Northwest as did many Black families in the 1930s through 1970s, settling into the segregated area of Seattle's Central District. Her childhood home was not an art house, but one filled with activities of functional yet meticulous decorative crafts her mother taught her, or fishing and gardening work she and her sister would do with their father. While she enjoyed working creatively, she never envisioned a future as an artist, nor did she know one could choose to do such a thing. A fundamental ethic in her family was getting an education and being self-sufficient.

Over a lifetime of creative discoveries, Thomas has produced paintings, glass sculptures, monumental immersive installations, and paper cut works that have been acquired locally and nationally by private and public collectors and institutions such as 21c Museum Hotel in Kentucky, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Henry Art Gallery, the Minneapolis Art Institute and the Portland, Seattle, Tacoma, and Weismann Art museums. Since the early 1980s, Thomas has produced work for over 50 group exhibitions and 20 solo gallery and museum exhibitions. She has also created approximately a dozen public works, soon to include a new stained-glass commission for Hopper College at Yale University in 2022, and her second commissioned installation at Seattle Sound Transit’s Judkins Park Station for 2023.

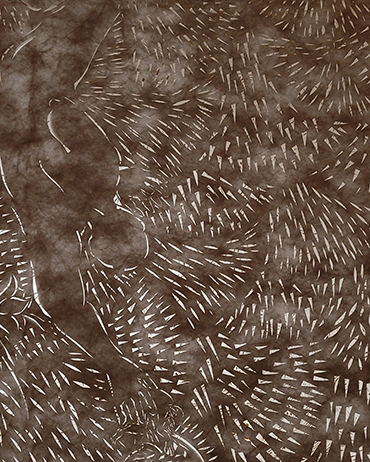

Though she has incorporated poems in her visual work, Thomas describes herself more as a writer of prose and travel stories, and she is still fluent in French after spending a year in France at the University of Grenoble in 1976. She has also authored principal essays for artist monographs such as Cappy Thompson and Joe Fedderson, but her principal materials and tools are paper, knives, paint, Tyvek (synthetic high-density material typically used as a weather barrier for buildings in construction), glass, metal, color pigments, and illumination. Thomas creates cuts to reveal exquisitely complex compositions of light and dark. Her works are graphic yet delicate, subverting the violent and divisive storylines of our social and political times into fluid metaphors of brighter possibilities.

Thomas works with a team of cutters, artists, cultural practitioners, and friends who help to bring, as she says “the results my thinking” to life. And her thinking reflects an avid reader concerned with “what is happening in the world.” Rather than representing pain however, she offers a lovingly tender elevation of Black people and their stories. Experiencing her installations is akin to entering a kaleidoscopic world of shadows with strange yet immediately familiar forms, tones, and textures, drawing us into a communal prism of inverted self-reflections.

Thomas’s masterful poetics have been on view in two recent and concurrent museum exhibitions in Washington. Her solo installation Geography of Innocence at the Seattle Art Museum (Nov 2020 – Jan 2022), selections of which are set for an east coast tour in 2023, examines the harmful projections of adulthood and criminality projected onto Black children, which she reconfigures through paper-cut highlights of their faces that suspend your breath as you are directed to refigure your own gaze — to see their innocence. Currently at Henry Art Gallery on the UW Seattle campus is Packaged Black (October 2, 2021 - May 1, 2022), a collaboration with celebrated artist and painter Derrick Adams. Together over a course of two years, Adams and Thomas developed a new series of visual conversations that playfully invite us to interrogate and then release our normative expectations of performance, beauty and dress as they pertain to outsiders, to Blackness, to exclusive adornments and commodity, and ultimately to our right to inclusion, play and safety. Aside from the apparent labor, meditation, and time it took to do this work, indeed it is a layered love story to their communities.

Adams and Thomas met at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2015 during the opening of Jacob Lawrence’s epic narrative 60 panel exhibition, One-Way Ticket: The Migration Series. Save for the legacy work within his eponymous gallery also on the UW Seattle campus — which hosts an arts writer incubator, Black Embodiments Studio led by Kemi Adeyemi, and an annual Legacy Residency for Black artists from around the country led by gallery director Emily Zimmerman — it is not widely known that Jacob Lawrence was a tenured professor at the UW for the last 25 years of his life. For much of that time, he was the only Black professor and faculty of color in the School of Art. It is also notable that Thomas’s current show at the Henry Art Gallery is her first exhibition on the University of Washington campus, as she was not included in her MFA Graduation show. While reinforcing the vitality of his lasting critical influence and presence in contemporary and historical art discourses, the quiet around Lawrence’s local representation reverberates through institutional corrective measures of accounting for the creative and intellectual contributions of Black artists, particularly here in the Pacific Northwest. Thomas readily speaks to and holds his memory in accessible regard. Both Lawrence and Thomas’s work were concurrently on show at the Seattle Art Museum in Spring 2021, with his The American Struggle exhibition a floor above her Geography of Innocence gallery.

Thomas recalls being one of approximately 300 Black students at the UW out of an estimated 30,000-plus students enrolled, some of whom were recruited after the UW was at risk for losing federal funding due to low Black enrollment. When she met Lawrence as a newly hired tenure track faculty, she did not know who he was and could not grasp the relevance of being called out of class by the Dean to meet him, assuming that it may have been a “black thing” since there were so few of them on campus. It was later, when she used her art class prize winnings to travel to Washington DC for a visit to the Smithsonian, that she encountered his works and understood the caliber of artist that she had immediate access to back home. There is a disciplinary poetic of practice gained from his mentorship, “an elegance in restraint, repetition, and specificity with color, line, and value which he taught me to identify for myself,” she says. But Thomas's style is distinctly her own which she honed over series of self-assignments in the years after leaving school, ensuring that her skills could serve her ideas and the work she wanted to make.

For artists listening to Thomas, her anecdotal stories are instructive. She understood early that after graduating she had to create her own methodologies and workflow, recognizing that “I'm the only one who would care if I did this or not, no one was going to check on me to see if I was making work.” She rejected invitations to participate in what she refers to as “lack of” shows, where being regarded only by her race and not by her ideas or proficiency would limit her, maintaining that “being Black is not a curatorial statement.” She put herself on a series of working assignments to go deeper into the variation of greys, of color, of paint textures, of illustrative lines, compositional design, and later, the unmistakably unique painterly cuts we now know her for.

This all seems a clear plan from the start, but Thomas explains that she didn’t really have one, or an identity attached to what she was doing, “For the longest time I didn’t even call myself an artist, I just said ‘I’m a maker — I make things.’” Even the word practice as it is used today was not how studio output was referred to in the Pacific Northwest in the 1980s. “I just made sure that I always made work. Everyday. If I had an hour, I would make for an hour.” Any available time was used to problem-solve a skill she was trying to master. “Life is what happens when you get past the plan,” Thomas notes.

Quite remarkably Thomas worked full time while in school to keep her student debts manageable, and for nearly 20 years she had a full-time career in arts administration while balancing her practice. She ran community arts programs for the Seattle Arts Commission, acted as programs coordinator for the Bumbershoot Festival Commission, and did marketing for Elliot Bay Book Company. She started out at the Northwest African American Museum (NAAM) in 2005 as Program Developer, leaving in 2012 after serving as the museum’s Executive Director in her last four years at the institution.

In this period, young artists and administrators benefited from her leadership. Many have gone on to serve at current Seattle institutions: 4Culture’s Executive Director, Brian Carter, and Heritage Program Director, Chieko Phillips; UW’s Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for Advancement, Leilani Lewis; and artists and Wa Na Wari co-founders Elisheba Johnson and Inye Wokoma. A few of those she worked with hold a presence in her practice either as cutters from her studio or central figures in her portraits. To round off such an impressive feat of support for and from her community, in 2009 Thomas and Sandra Jackson Dumont (current CEO and Director of Lucas Museum of Narrative Art) co-formed Seattle Art Museum’s Gwendolyn Knight & Jacob Lawrence Prize, which biennially celebrates early career Black artists with a significant cash award and solo exhibition at the museum.

Thomas’s active outlook on how we work, tell stories, and hold each other up is evinced in the archival portraitures of her people — some of whom are recognizable artists, performers, writers, and cultural practitioners. “Barbara is a national treasure, and we are so grateful to have her in our very own community,” says Jazmyn Scott, director of Programs and Partnerships at Langston Seattle. “The essence of her joyous personality adds to the transcendence of her incredible artistry. I have been honored not only to experience her creativity over the years, but to be included in her most recent exhibition. I continue to learn from and be inspired by her every day."

There is a poeticism in how Thomas translates this love and celebration of her people, seductively employing beauty to engage uneasy stories that arrest her attentions about our nation’s troubling times — and particularly those that befall the Black community. But Thomas also lives for inventing new imaginaries. She recalls being moved by words of author Ta-Nehisi Coates during a crushing time in 2020, at the height of a double pandemic of Covid-19 surges and the eruption of masked Black Lives Matter protestors in the streets following the gruesome public murder of George Floyd and numerous innocent Black people. Coates said, “I’ve never felt more hopeful.” It stunned her heart. It was a frightening and wretched time, and yet it was also an insistent time to continue to live on — to resist cynicism and despair, to embrace a belief in our common humanity within the shards of evidential disconnection. It is a poetic bridge we cross over time between Geography of Innocence and Packaged Black, between grief and dreaming. From a lifetime of chance, precision, risk and wonder comes a formidable grace in her daily discoveries and practice. Thomas is quite plainly herself, present and grounded by her inner compass, which is uniquely disarming in a world that seems to demand performative caricatures of authenticity. Thomas challenges us to hold an existence beyond the laments of the world and offers space for a determined departure from limited racialized identities to boundless possibility of human imagination.

Berette S Macaulay is an interdisciplinary artist, independent curator, and writer based in Washington state. She currently serves as Art Liaison Program Manager at the Henry Art Gallery, the Curatorial Fellow at On the Boards, and founder and lead organizer for Black Cinema Collective, a project of i•ma•gine| e•volve. www.berettemacaulay.com.

Macaulay visited with Barbara Earl Thomas in her studio on December 10, 2021 to interview the artist for this series. All quotes are from the transcript of their conversation and subsequent conversations by phone.

Unless otherwise noted, all images of artworks and exhibition installations are courtesy of the artist and Claire Oliver Gallery.

More Stories

Finding Love at the UW

They met and fell in love as UW students. Here, 10 alumni couples share how they met, their favorite spots on campus, and what the UW still means to them.

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.

A Love of Classics and Ballroom

Michael Seguin studied Classics at the UW and now owns Baltimore's Mobtown Ballroom. The two interests, he says, are more connected than they might seem.