Recent efforts to dismantle affirmative action and critical race theory have been helped by a controversial political block: Black Republicans. They have been vocal in supporting their party’s position on racially charged issues. That might puzzle some people, but not La TaSha Levy, whose research focuses on the complicated relationship between African Americans and the Republican Party.

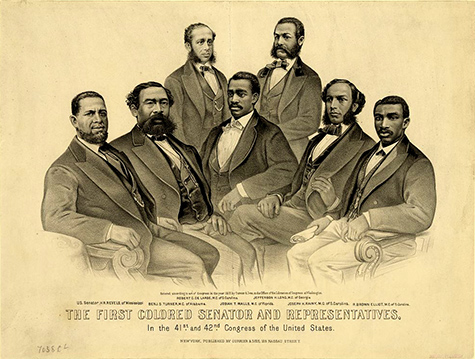

Levy, assistant professor of American ethnic studies and adjunct assistant professor of history, explains that the Black community’s support of the Republican Party dates back to the 1860s.

“Black people were overwhelmingly Republican after the Civil War and Reconstruction, because the Republican Party was the party that fought for the abolition of slavery— the ‘Party of Lincoln,’” Levy says. “For generations, so many Black families couldn’t fathom being Democrats, since that was the party of white segregationists and white supremacists.”

A major shift occurred in the early 20th century when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt introduced the New Deal. The Democrats’ push for social welfare reform challenged African Americans’ loyalty to the Republican Party, and many African Americans voted for a Democratic president for the first time. Still, a significant portion of the Black community remained loyal Republicans.

“Eisenhower was able to attract more than 25 percent of Black voters in the late 1950s,” says Levy. “When Richard Nixon ran for office in 1960, he was able to attract 32 percent of the Black vote. Black people were still very active in the Republican Party, especially on the state and local level.”

That loyalty would once again be tested again a few years later. Levy’s current research looks at the period from the height of the Civil Rights Movement through the late 1980s, when the landscape for Black Republicans took a dramatic turn.

A Dramatic Party Realignment

“Good grief, it’s messy,” Levy laughs as she launches into an explanation of the complicated shift in Republican politics. Levy explains that African Americans on both sides of the political aisle had long shared an interest in supporting civil rights and Black economic empowerment, often with cross-party collaboration. But when Barry Goldwater became the Republican presidential nominee in the mid-1960s, with views that led to endorsements from the Ku Klux Klan and the John Birch Society, Black Republicans were shaken.

“It was a slap in the face to Black people who had been loyal to the Republication Party as the party of Lincoln,” says Levy.

In the decades that followed, the party went through a dramatic realignment that further tested that loyalty. “It started to position itself as the party of white America — maybe not saying so explicitly, but there’s a lot of documentation of the party trying to attract disillusioned white Democrats,” Levy says. “There was a whole campaign to reinvent the Republican Party. To do that, the party pushed an ideological agenda that framed white men as the new victims of institutional racism.”

What it meant to be Black and Republican started to shift, and moderate Black Republicans had to deal with the contradictions.

Conservative think tanks and foundations like the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Hoover Institution emerged as influential players in what Levy calls “the battle of ideas” — a term first popularized by Ronald Reagan — that drove the Republican Party’s political realignment. Those groups promoted rhetoric designed to help pass policies that were a hard sell, such as working to dismantle affirmative action by calling it “racial preference.” And they cultivated Black political conservatives — not to be confused with Party-of -Lincoln Black Republicans — to share their message.

“Black people have played such a significant role and often they’re not mentioned in the scholarship on the rise of the modern conservative movement,” says Levy. “To have a Black person espousing the idea that Black people are filling up our jails because they come from single parent homes and they’re gangsters and drug users — it does mean something for a Black person to advocate those ideas in ways that would be considered outright racist if espoused by white folks. The party was able to make some extraordinary shifts by elevating people from marginalized communities to legitimize the policy initiatives and rhetoric that demonize those groups.”

Navigating a Changing Landscape

Those “extraordinary shifts” left liberal and moderate Black Republicans in a quandary. Those who had pushed for the party to be more responsive to African American interests now found their party attempting to erase those efforts.

“The tone and posture of Black Republican politics recalibrated to accommodate, rather than counteract, a rising conservative movement within the GOP,” says Levy. “Black Republicans who were fighting for affirmative action and racial justice were shut out. Looking at the record, so much of the politics of Black conservatives aimed to delegitimize the work that more moderate or liberal Black Republicans had been pushing for generations.”

Why would African Americans choose that contrarian role? For some, it might reflect long-held personal beliefs. For the rest, Levy has several theories. One is the lure of influence and prestige. By serving as spokespersons willing to toe the party line, they gained access to power and prestige and visibility. Also, since the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans had entered politics in larger numbers. Most were Democrats, which meant it was easier to climb the political ladder as a Republican.

But what interests Levy more are the experiences of the other Black Republicans — those whose voices were drowned out by the Black conservatives invited to speak in meetings and in the media. “What it meant to be Black and Republican started to shift, and moderate Black Republicans had to deal with the contradictions,” she says.

Levy is completing a book about this political shift and is gathering personal stories of liberal Black Republicans who lived through it. “It’s important to shed light on their journeys as they navigated the racial terrain within the Republican Party during a very tumultuous time in our country,” she says.

Levy looks forward to sharing what she’s learned with audiences beyond academia.

“I do this work for my sister and my mother-in-law and my godmother,” she says. “I do this for everyday people, to help them understand how racism shapes our political system. I hope that the way I bring attention to political communication and antiblackness helps to explain how we got here, how we strategize, and what we can do to fight for the world we all deserve.”

La TaSha Levy is currently creating a website (set to launch in ealry 2024) highlighting Black Republican advocacy for affirmative action and other race-conscious policies in the period prior to the elevation of Black conservatives in the 1980s. Among those featured is the ‘father of affirmative action,’ Arthur A. Fletcher, a Black Republican who began his political career in Washington state and remained committed to affirmative action even when his party mobilized resistance to the policy.

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Sports Obsession Inspires a Career

Thuc Nhi Nguyen got her start the UW Daily. Now she's a sports reporter for Los Angeles Times, writing about the Lakers and the Olympics.

A Healing Heart Returns

In February, the UW Symphony will perform a symphony that Coast Salish elder Vi Hilbert commissioned years ago to heal the world after the heartbreak of 9/11. The symphony was first performed by the Seattle Symphony in 2006.