Peek into Adrienne Mackey’s DRAMA 480 classroom this spring and you’ll find students playing board games. And role-playing games. And video games. Beneath the fun of game play, the students learn how game design influences interactions between players — and how similar techniques might be used in theater productions.

The course, Game Design in Live Performance, is offered by the University of Washington School of Drama. Mackey developed the course soon after joining the UW College of Arts & Sciences as an assistant professor of acting, directing, and devising in 2021.

“I like creating theater experiences where the audience can make choices as they move through it,” says Mackey. “That empowers people to feel like a performance is in some part theirs, as opposed to a more traditional play where you just sit and receive. But how do we get audiences involved without giving over to chaos? Game design offers tools and systems that can help.”

Rules of Engagement

Mackey defines participatory or interactive theater as productions where the audience is actively engaged in some way. That might mean walking between groups of actors performing in a non-traditional space, or joining in as a character, or something even more unexpected. Mackey has pushed the boundaries of participatory performance for years as artistic director of Swim Pony Performing Arts, a theater company she founded in 2009.

Producing interactive theater, Mackey quickly learned that clarifying rules for audience participation is essential. “I started to understand that structure and rules help people learn to participate better,” she says. “You may have spent months understanding the rules of the world of your play, almost like creating a mini culture. And then you bring an audience into that and they have minutes to understand. So of course you need to teach them. It’s like going to another country and learning the customs. You need time to acclimate to the norms of that world.”

Finding ways to introduce those norms can be tricky. That’s where game design comes in.

Mackey enlisted a friend, a videogame writer, to lead a workshop for her theater company about techniques videogame designers use to introduce players to the world of a game and its rules. “The workshop blew my mind,” Mackey says, recalling the many connections she saw between game design and participatory theater. Soon after, she pursued an MFA at Goddard College, where she studied the core principles of game design and researched theater performances that use game-like interactive techniques.

...How do we get audiences involved without giving over to chaos? Game design offers tools and systems that can help.

Since coming to the UW, Mackey has continued to explore game design as a tool for interactive theater. And she’s been eager to share her perspective with students. “I’ve been interested in how to codify some of the things I’ve been doing in my own company as a practice students can learn,” she says.

Agency for Audiences

About half the students in Mackey’s course are drama majors. Many others are STEM students. Mackey considers that combination “a superpower” of the class.

“Both kinds of students, and the way they have learned to think and shape problems, really dynamically impact each other,” Mackey says. “Every time I’ve taught the class, there has been a lovely cross-pollination in thinking and learning that happens. It’s one of the reasons I was excited to come to the UW rather than teaching at an art school.”

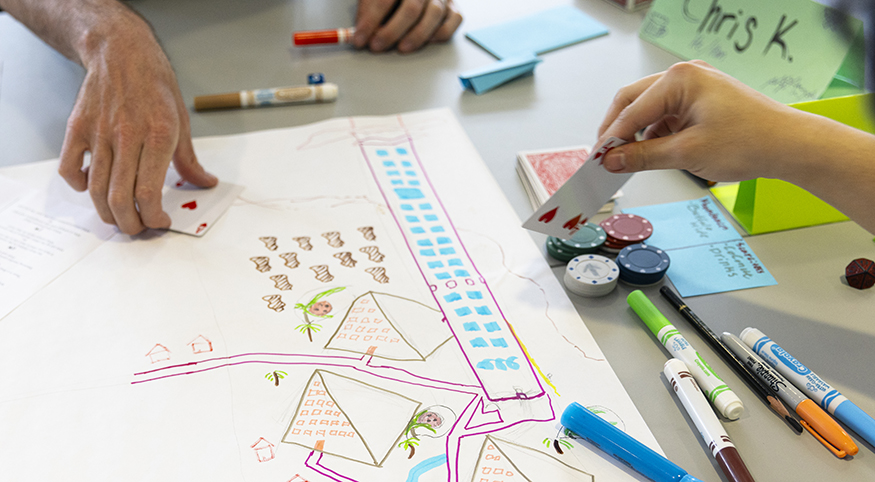

Each week, Mackey introduces a different aspect of game design in a lecture and hands-on sessions. She has the students play games — analog games like Monopoly as well as digital and video games — to underscore the week’s concepts. “I go deep into some of the specifics of how game designers and theater makers do this, and then the class has a chance to practice that experientially,” Mackey says.

Mackey focuses on the mechanics of games — how rules are introduced and how those rules encourage players to interact — before moving on to storytelling, character development, and related topics. Throughout the quarter, students complete four increasingly complex projects, from creating a simple game that relates to some aspect of their life, to designing an interactive experience that casts one or more audience members as characters within the piece. For their final project, students rework a past project or create a new one.

The Challenge of Non-Linear Narratives

Sammy Weinert, a drama major and linguistics minor, found the assigned projects challenging in the best possible way. “In performance classes, you are taught how to practice theatre — how to analyze a scene and a character, how to rehearse and embody a story written by someone else,” Weinert says. “But this class teaches you to create. You are taught to build something from the ground up without fear of failure, and then how to tweak and adjust it to achieve your goals. This is terrifying but ultimately immensely satisfying and useful in all parts of your life.”

Weinert’s final project with classmate Anna Shih was a sprawling interactive “audio-scape” that led players across the UW campus as they listened to stories about two fictional UW students from the 1930s — and heard from the ghosts of those students. The interactive experience provided multiple routes for the players, with the potential to help resolve a personal matter between the two ghosts.

“Creating this game not only taught me what a massive undertaking it is to create a non-linear narrative, but also how powerful it is to give an audience or player agency to shape the story they are experiencing,” says Weinert. “It massively increases the potential to affect them.”

Since taking Mackey’s class, Weinert also has a new appreciation for games in general.

“Games are a core aspect of being human, but one we often look down upon as childish and inconsequential,” Weinert says. “By viewing the world through the lens of game design, you can bring beautiful interactivity to your art — and inject joy into the mundane moments of your everyday life.”

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

Bringing Music to Life Through Audio Engineering

UW School of Music alum Andrea Roberts, an audio engineer, has worked with recording artists in a wide range of genres — including Beyoncé.