Abdullah Bhurgri and Rhonda Osman dreamed of becoming doctors since childhood. Osman joined the Minority Association of Pre-Medical Students (MAPS) as a UW undergraduate; both Osman and Bhurgri secured spots in BIOL 310: Survey of Human Anatomy, an undergraduate course for biology majors.

“Anatomy provides the most hands-on medical experience an undergraduate can have within biology,” says Osman (BS, Biology, 2022).

That is particularly true at the UW, where undergraduates get to work with human cadavers, referred to as donors — an opportunity not available to undergrads at many US schools.

For Bhurgri (BS, Biology, 2021), that anatomy class was a turning point. He had previously struggled to imagine himself as a doctor due to a lack of representation in his community. “BIOL 310 was the first time that my journey truly clicked for me,” he says. “It was such a formative experience for both Rhonda and me. Working with the donors in the anatomy lab provided us with a unique and humbling experience that truly affirmed us in our pursuit of healthcare.”

We try to really engage the participants in how anatomical knowledge is not just memorization. It is a thought process.

Osman and Bhurgri thought other students underrepresented in healthcare fields would also benefit from an anatomy experience, but the undergraduate anatomy course is limited to a small number of majors and fills within minutes. That led them to co-found Anatomy for Change, a program that provides anatomy workshops for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and first-generation students, as well as students from other underresourced communities. The hope is that by experiencing an anatomy lab and working through medical case studies, the students will gain confidence in pursuing careers in healthcare.

Hands-on Anatomy Lessons

Though Bhurgri and Osman had a vision for Anatomy for Change, they needed a faculty sponsor to help realize that vision. Bhurgri, who had served as a peer facilitator for BIOL 310, presented the idea to instructor Casey Self, associate teaching professor in the Department of Biology.

“Abdullah came to me with a PowerPoint presentation,” Self recalls. “He was really worried I was going to say ‘no.’ Instead I told him I’d been wanting to do something like this forever. I was a McNair Scholar and EOP (Educational Opportunity Program) first-generation college student, so I have strong feelings about expanding the experiences available to students like me. I just didn’t have the time to organize something myself. I loved that this program would be student driven.”

With Self on board, Osman and Bhurgri began planning their first Anatomy for Change workshop, drawing inspiration from the team-based learning exercises that Self incorporated into her course. A UW Diversity and Inclusion Seed Grant helped compensate Osman and Bhurgri for their efforts.

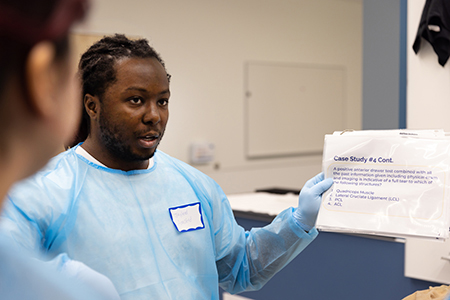

The pair developed a two-hour workshop in which participants rotate through eight “stations” focusing on different regions of the body. Knowledgeable volunteers — including UW medical students and peer facilitators — oversee the stations. After providing a brief anatomy lesson specific to that station, the volunteers present a hypothetical health problem to the participants, sometimes sharing CT scans or x-rays. Then, using what they’ve just learned, the students predict outcomes for the “patient” and suggest additional diagnostic tests that might be helpful.

“We use little snippets of the curriculum I designed for the anatomy course, modified to be accessible for students not majoring in biology,” says Self. “We try to really engage the participants in how anatomical knowledge is not just memorization. It is a thought process. It’s important to empower students with the idea that they can think about anatomy, they don’t just have to memorize anatomy.”

The workshop, held in the anatomy lab in the UW’s Heath Sciences Education Building, has now been offered three times. The participants — up to 35 students per workshop — have the opportunity to interact with donor cadavers just as students in anatomy classes would. All participants have been respectful of the donors.

“If anything, they’re reluctant to do too much because they worry about being disrespectful,” says Self. “Everybody’s a little nervous, which of course they should be. But sometimes to understand something, you have to take it apart. I remind them that these gifts were freely given [through UW Medicine’s Willed Body Program] with the intent of shaping our future medical professionals — which is them. So whatever they need to do to learn from this gift, that is being respectful. And very quickly, they stop being scared or worried because it's so interesting.”

Medical Student Role Models

Having students from the UW School of Medicine on hand as volunteers is also impactful. Bhurgri and Osman have made a concerted effort to recruit medical students who — like the participants — come from underserved communities, to ensure that workshop participants see people similar to themselves in healthcare roles. The response from medical students has been so enthusiastic that there is a waiting list for those interested in volunteering.

Third-year medical student Abigail Melton has volunteered several times. Like Osman and Bhurgri, she had the opportunity to study anatomy as an undergraduate (at William & Mary), also in a lab with donors. She found the experience transformative. “I look back on the donors from that class as my first patients,” she says.

That experience made volunteering for Anatomy for Change an easy decision for Melton. “I wanted to participate to help facilitate the excitement for medicine that I felt when studying anatomy,” she says. “I want to be a part of that bridge for students by showing them anatomy up close, talking through cases, and answering questions about medical school.”

Bhurgri and Osman will soon be able to answer questions about medical school as well. Both will begin medical school at the UW in July. They will hand over the coordination of Anatomy for Change to new coordinators, Beatrice Asomaning (BS, Biology, 2023) and Emily Buak (BS, Biology, 2023).

Of course, Self will remain a constant as the program continues. But she is quick to emphasize that the key to the success of the program has been — and will continue to be — the commitment of undergraduates leading the effort.

“The program has gone smoothly because of the work of Abdullah and Rhonda, who felt passionately about it,” Self says. “They put the blood, sweat, and tears into creating these events. They just needed someone to remove the barriers and give them guidance when they needed it.”

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

Through Soil Science, an Adventure in Kyrgyzstan

Chemistry PhD alum Jonathan Cox spent most of 2025 in Kyrgyzstan, helping farmers improve their soil—and their crops—through soil testing.