The Gates Foundation spends millions to tackle malaria worldwide. American doctors volunteer their skills in war-torn regions. Nongovernmental organizations promote AIDS education in impoverished nations.

Inspiring? Absolutely. But global health initiatives like these also raise ethical issues, as they have for centuries. In a new course, Before Global Health, Adam Warren explores the history and politics of overseas health interventions, covering everything from the medieval Black Death to colonialism, the rise of international philanthropy to the Cold War.

“My hope is that by studying this history, students will develop a clear understanding of how the past informs the present in the global health movement, shaping both its achievements and its limitations,” says Warren, associate professor of history and Howard and Frances Keller Endowed Professor in History, whose most recent book focuses on colonial medical policies and interventions in Peru.

Warren first presents ancient Greek and Roman views on the body and health, to lay the groundwork for understanding how those views have changed. He then covers the plague in medieval Europe before moving on to European colonialism, a significant precursor to the contemporary global health movement. “When Spanish colonists arrived in the Americas, they brought with them smallpox and many other illnesses that led to massive depopulation,” explains Warren. “Studying these processes is a way to engage students in questions of how diseases actually shaped history. The colonists had to confront epidemics on a scale that was pretty unparalleled and threatened their whole colonial venture.”

The history of this field is a complicated history, but I think that students can be empowered by it and learn from it as they move forward.

Colonists in the Americas and elsewhere were often highly motivated to address epidemics, since a dwindling indigenous population meant fewer workers and less profits for the mother country. But colonists’ ideas about medicine and health often conflicted with those of the patients they were treating. “Colonialism brings together cultures that have very different ideas about bodies and disease and healing,” says Warren. “I wanted students to think not only about how colonists attempted to intervene, but also about how the people they were treating understood these intrusions into their daily lives.”

Warren finds that class discussions of colonialism are challenging but productive. “Colonialism is a difficult story that includes suffering and inequalities of power,” he says. “The logic of colonialism is about the supposed inferiority of the population being colonized from the perspective of the colonizer. A lot of students were shocked by the ways that colonial doctors have talked about disease in different populations.” He adds, “I’m not trying to accuse global health as a field of perpetuating colonial relations. Rather, I am trying to have students think about where this field comes from and how it is different now and how it might be different still in the future.”

Other historically significant moments covered in the course include the bacteriological revolution in the 1870s, when an increased understanding of germs led to new tools for disease prevention; the rise of medical philanthropy in the 20th century, with the Rockefeller Foundation taking the lead to improve health globally; the emergence of Cold War competition over development projects and international aid after World War II; and the AIDS epidemic as a global challenge in the context of neoliberalism.

“The Rockefeller Foundation laid the groundwork for much of how global health works as a field today,” explains Warren. “This is medical philanthropy on a global scale—the collaboration with nation-states to improve health by targeting specific diseases among their populations.”

Developing a new course that spans several millennia and continents was a challenge for Warren, but one he relished. “I’d been thinking about this course for years,” he says. “Some global health issues aren’t easily explored in science courses. I wanted to provide another venue for thinking about them in depth.” What finally made the course possible was a course development grant, funded through the Robert A. Nathane, Sr. Endowed Fund in History. Warren used the grant to attend a national conference on the history of global health—“it helped me rethink the entire course,” he says—and to purchase books related to the topic.

Warren plans to teach the course again Fall Quarter 2014, and hopes that it can become a regular offering in the department.

“This course enables me to reach students who will someday do really interesting things in global health,” he says, noting that the class attracted science majors and global health minors in addition to the history and Latin American & Caribbean Studies majors that normally take his classes. “Conversations about the history of global health should be a key part of their training. I think there’s a leap they have to make about how different cultures have understood disease and bodies and health. Moreover, we can all benefit from thinking critically about the politics of medical interventions. The history of this field is a complicated history, but I think that students can be empowered by it and learn from it as they move forward.”

More Stories

Making Art, Making Connections

While at the UW, artist Kyra Wolfenbarger was a researcher, museum intern, and arts writer. What shaped her most were the people she met along the way.

Exploring the World — and Global Careers

Study abroad in Vietnam and Madrid. An internship with the State Department. International studies major Grace Kelly explored the world as a UW student.

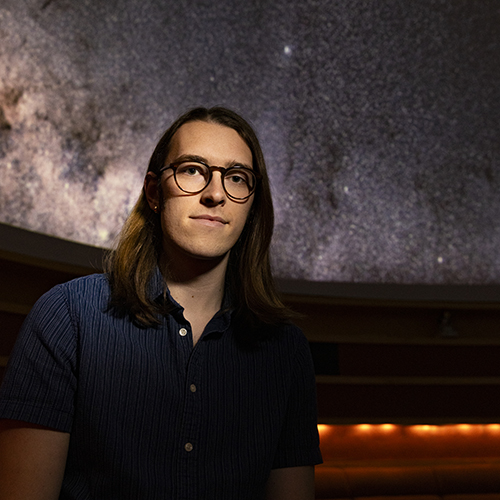

Tracking Comets, and Other Celestial Adventures

Using a powerful research telescope, astronomy and physics major Max Frissell identified a never-before-seen active comet. Now he’s hooked.