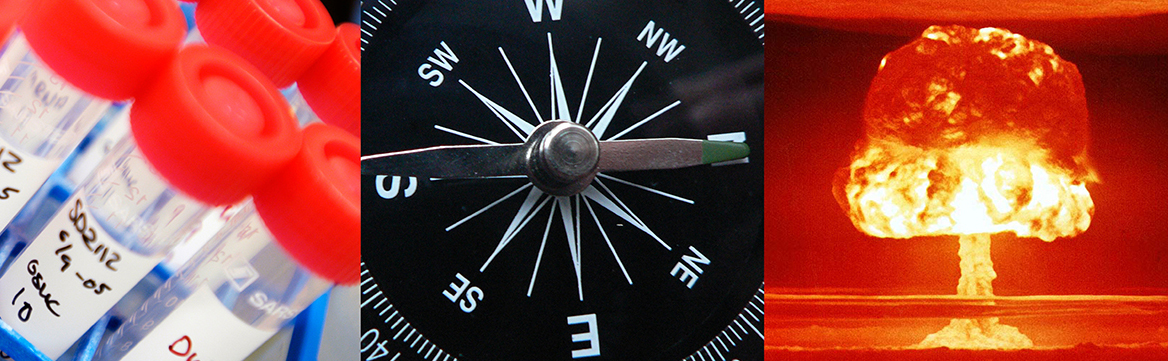

Every scientific advancement is about more than just the science. From evolutionary theory to the atomic bomb to genetic testing, scientific breakthroughs tell us about the prevailing world view and human nature. They raise ethical issues with enduring consequences. Exploring these aspects of science is the focus of the UW History and Philosophy of Science (HPS) program.

“History and philosophy of science comprises a set of ways to ask, ‘Why do we understand the world as we do?’” says Bruce Hevly, associate professor of history and a core member of the HPS faculty. “The subject teaches our students critical thinking in the very best sense.”

The HPS program was established in 2000 after several philosophers of science joined the UW faculty. The program expanded on an existing history of science program in the Department of History. HPS majors often pair their degree with a complementary major in history, philosophy, or one of the sciences. Many pursue careers in science or medicine.

While most HPS courses are based in one department, History or Philosophy, a capstone course is co-taught by professors from both departments. “The capstone is an integral part of the major,” says Andrea Woody, professor and chair of the Department of Philosophy. “It’s the one place where our majors study history and philosophy at the same time, in relation to the same material. Students often feel more at home in one of the disciplines, but in class with students from the other discipline, they realize ways their perspective has been limited.”

It’s very fun to bring different sets of assumptions and commitments into contact, and to let students see the faculty engaged in mystifying each other for a change.

That holds true for the faculty as well. “The capstone always leaves us with the feeling that the other person has such interesting things to say,” says Woody. “I could sit all day and listen to historians talk about the ways in which science has unfolded historically, and I think they appreciate the kind of conceptual clarity that philosophers try to add to that messy story.” Adds Hevly, “It’s very fun to bring different sets of assumptions and commitments into contact, and to let students see the faculty engaged in mystifying each other for a change.”

The capstone course explores a different topic each year, which can be challenging for the faculty teaching it. Yet they do so willingly, relishing the intellectual exchange. “The capstones are the hardest courses to teach,” says Woody. “I always have to strap myself in, because there is so much planning to be done to ensure the philosophical work properly engages with the historical work. But as an intellectual process, they are definitely my most satisfying teaching experiences.”

The experience is equally memorable for students. John Pyles (BA, Philosophy, HPS, 2002), now a research scientist specializing in cognitive neuroscience, was one of the first to earn an HPS degree. After initially declaring a physics major, Pyles took an introductory philosophy of science course and “immediately became fascinated.” He switched majors and graduated with degrees in philosophy and HPS. “Thinking critically in the way I was trained in HPS has made me a better scientist,” Pyles says. “It has enhanced my awareness of how my field operates and the critical issues facing us, and it has helped me avoid mistakes made in the past. I’m of the opinion that some training in history and philosophy of science should be a requirement of most scientific graduate programs.”

Thinking critically in the way I was trained in HPS has made me a better scientist.

Another fan of the program is Larry Robinson (BA, Chemistry, 1968; MD, 1972), a retired emergency room physician who began taking HPS classes as an Access Program student. (Through the Access Program, individuals age 60 or older can audit UW courses.) After auditing several history of science courses from Hevly, Robinson signed up for a philosophy of science class and loved that too. “Once you have taken a course taught by Professor Hevly, you will never see the world in the same way,” says Robinson. “And Professor Woody has the ability to make the most obtuse concepts understandable, something not so easily done.”

Robinson was so impressed with the HPS program that he made a generous donation last year, which funded a regional HPS workshop. The success of that workshop inspired him to make a larger gift to establish the History and Philosophy of Science Support Fund, which will fund an annual undergraduate essay prize named in honor of Thomas Hankins, professor emeritus of history and a founder of the original history and science major. The fund will support other HPS projects as well, with an emphasis on enhancing the educational experience for students. “Larry was adamant that he didn’t want his name on the fund,” says Woody, “because he wanted to encourage others to add to it.”

The fund already has a second donor. Lonnie Robinson (BS, Zoology, Chemistry minor, 1938), Larry’s father, recently made his own substantial donation. Lonnie, who celebrated his 100th birthday this year, still fondly recalls the philosophy courses he took as a UW undergraduate, including a course taught by Professor Savery, namesake of Savery Hall.

“We’re always trying to do more with less, so to have donors tell us they think our work is important and want to support what we do—that’s particularly gratifying,” says Woody. “This recognition and financial support will carry us a long way.”

. . .

Support the History and Philosophy of Science Support Fund.

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

A Sports Obsession Inspires a Career

Thuc Nhi Nguyen got her start the UW Daily. Now she's a sports reporter for Los Angeles Times, writing about the Lakers and the Olympics.