Expansive windows line the hallways of the new Burke Museum, inviting visitors to observe museum staff at work. In one lab, a preparator removes rock surrounding a fossilized T. rex bone. Down the hall, a colleague examines a naked mole-rat to be added to the research collection. Two floors below, a curator repairs a wood and seal-skin kayak. Keeping track of all these activities is Kate Fernandez (BA, Comparative History of Ideas, 2001), the museum’s director of interpretation and visitor experience.

Fernandez is able to share what’s happening throughout the museum at any given moment, encouraging visitors to view work in progress. “My job is to make sure that visitors’ experiences are meaningful from the moment they walk in the door,” she says. “We want them to feel welcome. We want to connect them to the work that we do.”

When Fernandez joined the Burke staff in 2016, the new building — which opened last month — was still in the planning stage. The design was underway with transparency as a priority, but the logistics of that transparency were still unclear. Fernandez was central to realizing that vision. “It was a little like jumping on a treadmill that was already going at a good clip,” she recalls of her arrival.

My job is to make sure that visitors’ experiences are meaningful from the moment they walk in the door.

Having a background in museum design helped. After a decade as a senior data collection manager for a UW research group and as a graphic designer, Fernandez developed award-winning exhibits at Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI). But the new Burke presented a very different challenge.

“We were building a see-through museum that would allow people to get up close to the work of the Burke and feel the magic of what happens in our collections,” says Fernandez, “but the staff were unsure how they were going to do that. They worried about feeling like they were on display, that they’d suddenly have to do a different job than the one they’d been hired for. So my first task, and this is where my work in research came into play, was to design an experiment that would allow us to prototype how we would do this.”

The experiment was “Testing, Testing 1-2-3,” an 18-month exhibition at the old Burke in which departments took turns going about their work in full view of museum visitors. The staff then provided feedback on the experience. “We did a lot of listening to hear what the staff’s fears and concerns were, and then created a protocol to respond to some of their issues,” say Fernandez. Her team also surveyed museum visitors about their experiences with the exhibition.

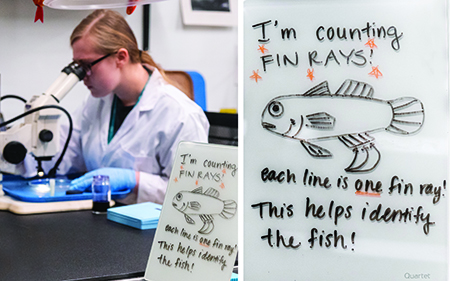

The experiment yielded some surprises, such as finding that visitors ignored the museum’s interactive signage in favor of simply watching staff work. That led Fernandez to scrap the signage and instead give each Burke team a small whiteboard on which to jot down what they were working on that day. The new approach was a hit, with the staff often adding doodles or humor to their descriptions. “That went a long way toward bridging the connection through the glass,” says Fernandez. Visitors to the new Burke will see informal whiteboard descriptions throughout.

Another surprise: many Burke staff were energized by their interactions with the public. “What was unexpected for them was the immediate reward and feedback you get when a visitor is delighted or inspired by what you’re doing,” says Fernandez. “It’s a wonderful thing that we get to share.” She offers the example of Jean (Prim) Primozich, a volunteer preparator whose work with a T. rex fossil led to the Prim Fan Club, a group of young girls who visited regularly to watch her prepare fossils and ask questions about her work.

In the new building, Primozich and other preparators and curators have the option to open their glass doors to speak with visitors when their work allows. The rest of the time, Burke volunteers are on hand to answer questions, share information, and point visitors toward additional activities worth viewing. The volunteers know what various Burke teams are doing throughout the day thanks to a digital communication initiative led by Fernandez. The information also is available in the museum lobby and on the Burke’s website.

With all these changes, the new Burke is quite different than the museum of Fernandez’s student days. As a UW undergraduate, Fernandez majored in Comparative History of Ideas — its emphasis on working across disciplines was “satisfying and intriguing,” she says — but she barely set foot in the Burke despite free admission for University of Washington students. “It wasn’t on my radar,” she admits. She hopes the new Burke will attract more students along with the general public.

“Museums have a big responsibility by providing and sharing knowledge about the world around us,” Fernandez says. “Race and equity, climate and the environment—these pressing issues are central to the work that we do. We plan to offer more engagement opportunities for young adults, including after-hours programming. We want everyone to see the Burke as a place that is central and relevant to their lives.”

More Stories

Finding Love at the UW

They met and fell in love as UW students. Here, 10 alumni couples share how they met, their favorite spots on campus, and what the UW still means to them.

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

A Love of Classics and Ballroom

Michael Seguin studied Classics at the UW and now owns Baltimore's Mobtown Ballroom. The two interests, he says, are more connected than they might seem.