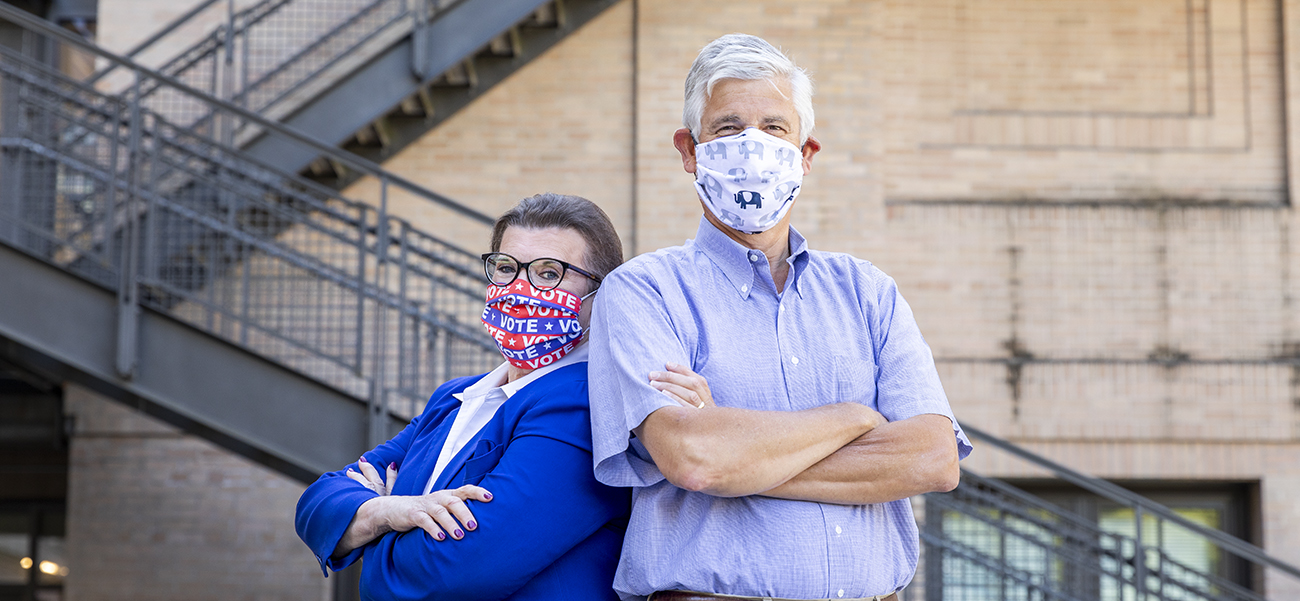

Think Democrats and Republicans can’t find common ground? Consider Republican strategist Randy Pepple and Democratic strategist Cathy Allen, who created and co-teach a UW course on political campaigns.

Pepple and Allen first met in the 1990s, when KUOW invited them to present opposing viewpoints in a radio segment. Their respectful rivalry led to more appearances on radio and television — and a true friendship.

“I come from old school politics where you fight like hell to win, but at the end of the day if you can’t have beer with the people you’re competing against, there’s something wrong,” says Arts & Sciences alumnus Pepple (BA, Political Science, 1984).

After regularly serving as guest speakers for a UW course on state government, Pepple and Allen approached Department of Political Science chair John Wilkerson in 2018 about creating a course on political campaigns. They have since taught Political Science 299: Modern Political Campaigns three times, most recently as an online course during spring quarter. Those enrolled range from first-year students to seniors, with a wide range of political views.

“The experience was great,” says political science major Rico Romo, when asked about having strategists from competing parties teach the class. “When one was speaking on an issue, the other would throw out their viewpoint and vice versa. They would tease and joke with each other, lightening the mood on touchy subjects.”

Allen and Pepple set that tone right from the start. “In the first class I tell students, ‘Look, Cathy is one of my closest friends. She’s wrong about everything, but I can overlook that,’” says Pepple. “And then,” adds Allen, “I’ll say, ‘Randy has two beautiful daughters and a wife he treats beautifully. Beyond that his values are terrible.’ We do joke to humanize each other and make it a little bit funny.”

Learning from Current Campaigns

After that introduction, the two instructors get down to business quickly, introducing students to the complex strategies involved in political campaigns, from messaging to image to fundraising. To bring their lessons to life, they have each student track a current candidate’s campaign throughout the quarter, analyzing the strategy and messaging. For some assignments, students take on the role of chief political consultant for their chosen candidate, recommending strategies for achieving specific goals.

Candidates don’t compete in a vacuum. You have to understand why the other side is doing what they’re doing if you’re going to defeat them.

Romo, who took the course in spring 2019, chose to track Senator Amy Klobuchar’s then-active presidential campaign. He studied Klobuchar’s stance on key issues and prepared weekly updates that often reflected the current class topic. For the final, he and his classmates presented speeches outlining why their candidate deserved to win.

“After my speech, Randy and Cathy asked follow-up questions as if they were press at a real press conference for the candidate,” Romo recalls. “The assignment changed the way I think about campaigns. You have to say the right things, talk in a specific way, and speak of the issues that can sway voters to your candidate. You are representing your client, and the details matter.”

When Negative is not Negative

Long before that final assignment, Allen covers the fundamental principles of persuasion — critical to any campaign — and outlines four major models of persuasion. She then tasks the students with applying the models outside of class. “We ask the students to find a situation in which they attempt to persuade someone over the course of a week, and then report back on the characteristics of persuasion they used and the result of their efforts,” says Allen. “Persuasion is not just about getting people to listen to your point of view; it is about influencing them to take action.”

The students’ successes have ranged from humorous to life-changing. One student persuaded her boyfriend to shave his legs; another persuaded his parents, who were steadfast in their belief that he should go to law school, to finally drop the idea.

While students in the class often have the advantage of surprise when they test persuasive techniques, a political candidate’s opponent is likely prepared with a counterargument. Which leads to another lesson: know your opponent thoroughly.

“Candidates don’t compete in a vacuum,” says Pepple. “You have to understand why the other side is doing what they’re doing if you’re going to defeat them. How do you take the strengths of your candidate and match them up so they exploit the opponent’s weaknesses? How do you undermine the opponent’s strengths? The course explores how to do that through a whole strategic framework.”

If that sounds negative, Allen and Pepple insist it is not. They dislike the term “negative campaign,” though they dedicate a class session to launching negative campaigns and another to responding to them. “We like to call those classes ‘Dishing it out and taking it,’” says Allen. “There are two different approaches here.”

Strategies the public might view as negative are, in Allen and Pepple’s view, an attempt to provide a contrast between the candidates. “Most students come in thinking that negative campaigning is terrible,” Pepple says. “We challenge them to think about what is an attack and what is contrasting the opponent’s position with your candidate’s position. If you’ve got a candidate who says, ‘I won’t go negative,’ the question becomes, are you ever going to say what you’ll do differently than your opponent?”

A Lifelong Connection to Politics

In this election season, the contrasts between some candidates may seem stark. But in local races, those differences can be more nuanced. Allen and Pepple invite current or former candidates from the Puget Sound region to speak to the class about their own campaigns, covering everything from their central message to — more recently — the challenge of addressing coronavirus, racial justice protests, and other controversial issues in the news.

While most students taking the course are unlikely to become political candidates themselves, or even campaign strategists, Pepple and Allen hope the course changes their experience of politics. “Many of them are likely to try being part of a campaign at some level, and some may choose to work in politics,” Pepple says, “but at the bare minimum, we hope the course piques their interest so they follow campaigns for the rest of their life.”

Adds Allen, “A lot of what we teach are life skills — how to convince someone, how to ask for money, how to actually organize people so that they come back and help you get a project done. So many of these things are skills that we’re going to need in a post-pandemic world.”

. . .

That life skill of learning to ask for money? We’re on board! The Department of Political Science welcomes private support to fund courses like Political Science 299: Modern Political Campaigns. Gifts can be made to the Friends of Political Science Fund.

More Stories

Finding Love at the UW

They met and fell in love as UW students. Here, 10 alumni couples share how they met, their favorite spots on campus, and what the UW still means to them.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.