Andrew Glass can trace his interest in Asian languages back to a cocktail umbrella. More specifically, the recycled newsprint visible on the inside of cocktail umbrellas made in China, Korea, and Japan. As a grade schooler, he marveled at the unfamiliar writing systems, nothing like the Roman alphabet he grew up with in the United Kingdom.

“I used to collect the insides of those umbrellas,” Glass (PhD, Asian Languages & Literature, 2006) recalls. “The paper was filled with these mysterious characters. It was like I’d discovered a secret.”

Glass is still fascinated by writing systems. Now a senior program manager at Microsoft, he works on font rendering and text input for Windows. In his personal time, he focuses on Gandhari, an ancient language he first encountered as a doctoral student at the University of Washington.

“I like to think of my day job as making my academic interests possible, and my academic interests making my day job possible,” he says.

The Perfect Project, on Birch Bark

Glass is most drawn to the physicality of language — the shape of letters, how they interact, how their appearance can vary depending on the scribe. By high school he had developed an interest in Sanskrit, which he studied — along with Tibetan language and Buddhism — at the University of London. Graduate study seemed to be the logical next step, if Glass could find a program that reflected his very specific interests.

Then came the Early Buddhist Manuscripts Project.

Around the time Glass graduated from college, the earliest known manuscripts about Buddhism, written on birch bark scrolls, were discovered after nearly two millennia. Richard Salomon, UW professor of Asian languages and literature (now emeritus), gained access to the rare documents and was leading a major research project about them. It was a perfect fit for Glass, combining his interests in Buddhism and Eastern languages. He joined Salomon’s research team as a graduate student in Asian Languages & Literature in 1997.

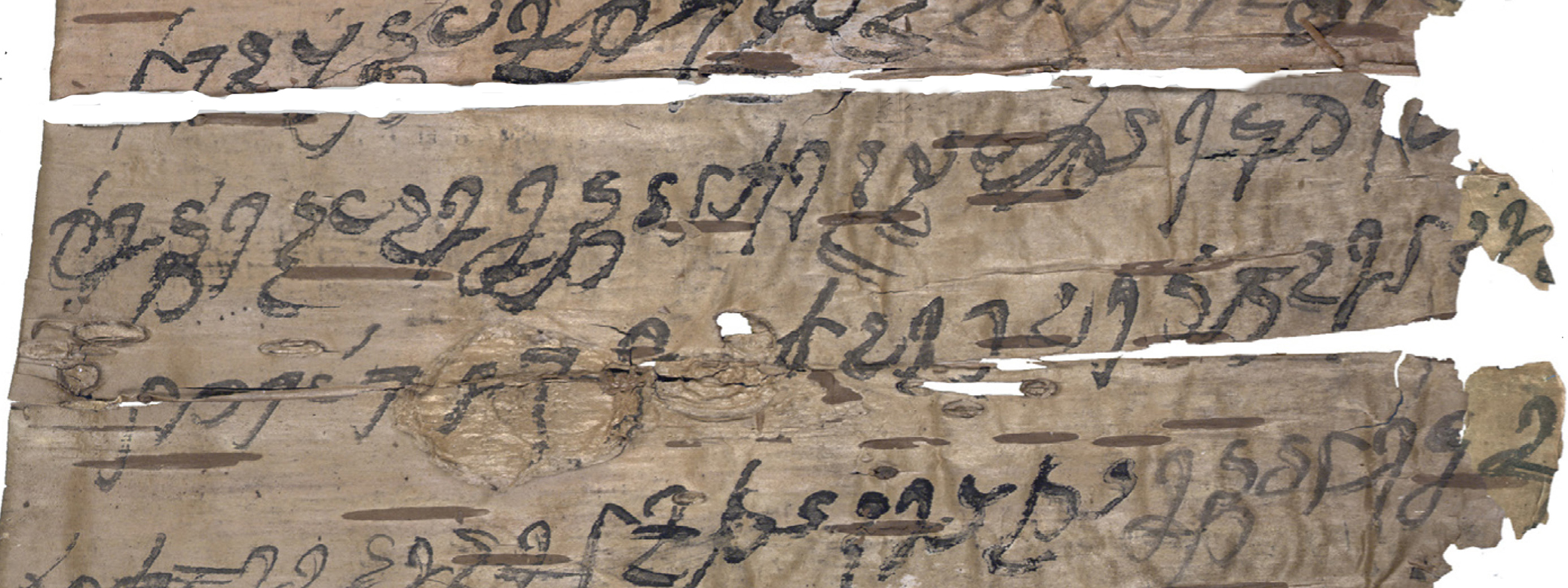

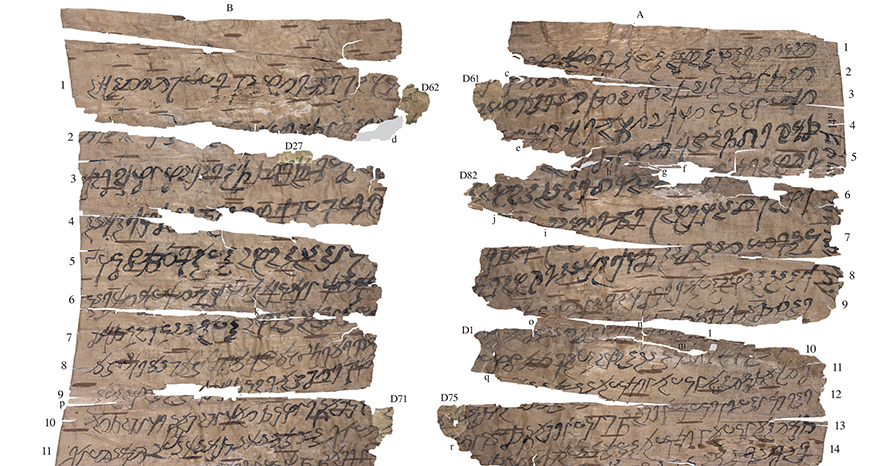

The ancient Buddhist scrolls were in fragments when they were found, so studying the documents required piecing them together. To complicate the challenge, the manuscripts were written in Gandhari, an unfamiliar ancient language related to Sanskrit. Many early Buddhist writings had been translated into Chinese and Tibetan as Buddhism spread, which provided helpful clues for deciphering the ancient Gandhari fragments. Glass worked closely with Salomon on many of the texts.

“We were a good team because Professor Salomon had knowledge of the texts and the languages, and I was very focused on the mechanics of the writing system,” Glass recalls. “One of my strengths was thinking about the physical movements of the hand on the paper, the shapes of letters and how their appearance varied in different locations, which helped with reconstruction of the manuscript from fragments.”

Glass wrote a master’s thesis on Kharoṣṭhī, the writing system used for Gandhari, and a doctoral dissertation on a manuscript containing four texts on meditation. The dissertation later became a book published by University of Washington Press in 2007.

Sharing Writing Systems Online

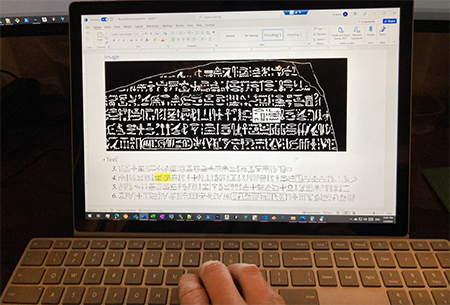

While Glass was channeling ancient scribes in his research, he was immersed in 21st century technology as well, developing a font for Kharoṣṭhī, the ancient Indian script used in the early Buddhist manuscripts. He presented a talk at Microsoft about Kharoṣṭhī, and later spoke about it with representatives from Unicode, an industry organization focused on the standardization of writing systems across platforms. A Microsoft manager who attended both meetings was impressed and recruited Glass for his team, responsible for font and script handling for complex writing systems in Windows.

At that time, the team worked on one writing system at a time, prioritizing widely used languages. Glass was asked to make a list of the known writing systems, to strategize how and when Microsoft would provide support for each. As Glass made the list, his hopes dimmed for Kharoṣṭhī being supported.

Writing started 5,000 years ago, but the journey is ongoing. The transition from writing into digital writing is another step in that journey.

“The writing systems with small user communities were low on Microsoft’s priorities list, which was absolutely the right decision for the business,” says Glass. “But as someone who specialized in a writing system that was read by 50 people at most in the world, I knew it would be decades before they would get to that.”

Slowing the process were Microsoft’s shaping engines, which power the correct display of complex scripts. At the time, each such language required its own engine. But four years into Glass’s time at Microsoft, he devised a universal shaping engine that could work with any writing system — including Kharoṣṭhī.

“That was fantastic progress and saved so much time,” Glass recalls. “One thing you learn working in the guts of something like Windows is that trying to do something that might seem simple, like rendering a language on the screen, is very complicated.”

Writing's Ongoing Evolution

Glass continues to work on a range of language projects at Microsoft, from ADLaM for Fulani — a language with 50 million speakers in West Africa — to Egyptian Hieroglyphics, used mostly by researchers. Each project requires collaboration with language specialists, and some are far more challenging than others.

“Egyptian is 20 times more complicated than the most complicated writing system that ships on Windows today,” Glass says. “It’s been a lot of work, but also a lot of fun to focus on that scale of a problem.” Outside of work, Glass’s main focus is expanding the online Gandhari dictionary he began co-editing as a UW graduate student.

Bringing together the ancient world and modern technology is second nature to Glass now. He shares his unique perspective as a guest lecturer in an Asian Languages & Literature course on the history and development of writing systems.

“Writing started 5,000 years ago, but the journey is ongoing,” Glass says. “The transition from writing into digital writing is another step in that journey. Through my work, I feel part of that transition. I believe it’s a significant moment in human history.”

More Stories

Finding Love at the UW

They met and fell in love as UW students. Here, 10 alumni couples share how they met, their favorite spots on campus, and what the UW still means to them.

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.