On a wintry afternoon, UW senior Mia Middleton pored over a leather-bound book from the 1700s. The early Enlightenment text, written in French, explored scientific questions for a general audience. As a biochemistry major and French minor, Middleton was intrigued. And then she wondered: Should the text be shared digitally for 21st century readers?

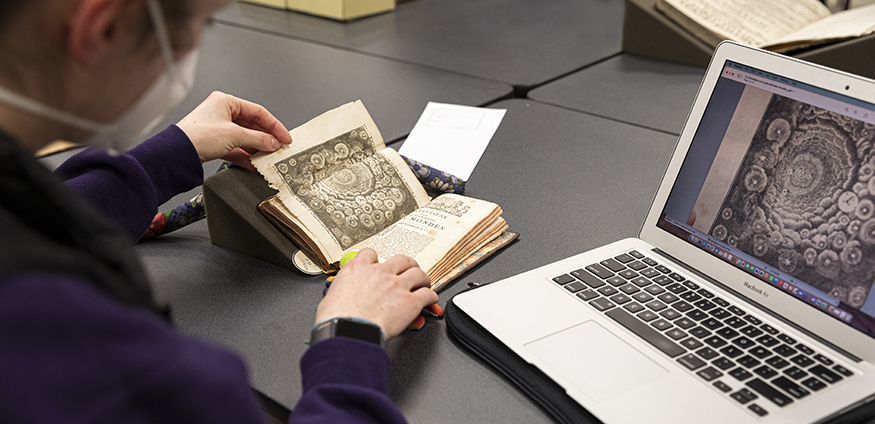

This was no random question. For the course “Text, Publics, and Publication,” Middleton and her classmates had to choose a printed text from UW Special Collections and transform a portion of it into a digital edition. The course, offered through the Textual Studies and Digital Humanities Program (see sidebar) and the Department of French & Italian Studies (FIS), explores the various forms texts have taken historically, and the impact of the digital revolution.

“Digitization has transformed the way we read, write, study, learn about the past, and conduct research,” says Geoffrey Turnovsky, chair of FIS and co-director of the Textual Studies Program, who teaches the course. “It has required a renewed reflection on what a text is, how it is shaped by publication processes and technologies, and how it can be reinvented over time.”

The Evolution of Texts

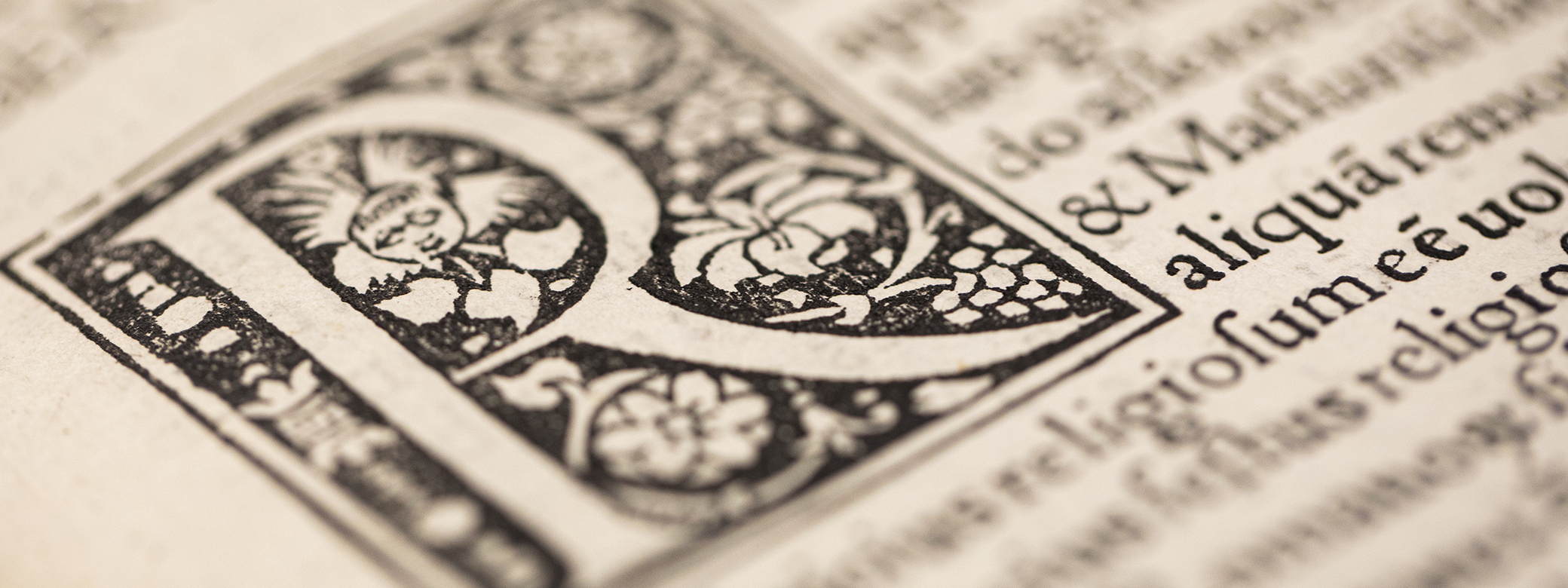

Digital technology is just the latest in a long history of advances that have changed the relationship between readers and texts. In late antiquity, papyrus scrolls were replaced by books with flippable pages. About a thousand years later, the introduction of the printing press launched another transformation.

Prior to the printing press, sharing texts meant copying manuscripts by hand, leading to a single additional copy at the end of the laborious process. Readers assumed and accepted that every copy was somewhat different. With the printing press, suddenly hundreds or thousands of copies could be created, with readers assured the content was consistent across copies.

“The printing press wasn’t developed to create more certainty, but that was one of the effects of it — that it created more trust in the written form,” says Turnovsky.

Digital technology has been another leap. Digital texts differ from printed books in how they look, how they circulate, and how we interact with them. The transition has not been without challenges; the digital revolution has once again raised concerns about consistency.

“Print seems fixed forever,” says Turnovsky. “Digital texts, like handwritten manuscripts, are not. They are more malleable, with more interactivity. We know exactly how to deal with printed sources, but initially — and I think this has changed — there was suspicion about citing electronic sources.”

From Print to Digital

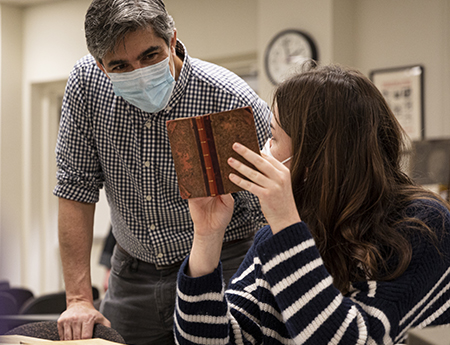

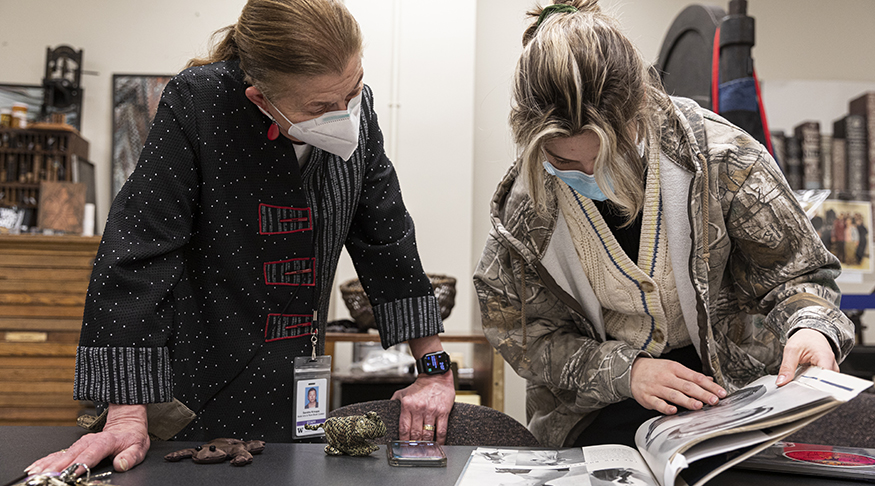

By creating a digital edition of a printed text, students in Turnovsky’s course discover the complexities of preserving a text in digital form. They also discover the exceptional resources of UW Special Collections, as Special Collections librarians Sandra Kroupa and Kat Lewis gather texts for them to consider.

“It’s a wonderful feeling to be holding a first edition of a book from the 1700s in your hands,” says Middleton of her time in Special Collections. “Kat and Sandra were so helpful and have so much knowledge not only about all the material, but also about the history of book making and book binding.”

Creating a digital edition is more involved than simply scanning the pages of a printed text and posting them online. After selecting a printed text to work with, the students manually transcribe their text — choosing ten pages or less — and then encode it using the XML-based guidelines of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) for online research and preservation. “I had absolutely zero knowledge of coding, so I was a little nervous,” says Middleton, “but I think the project really added another layer to our learning.”

The students decide what content to include in their digital edition, whether to mark up the typography and other visual features, and whether to “tag” words or place names in the text for easy reference. “You have to actively select the content you will incorporate, and that process involves so much decision-making,” says UW junior Alex Seo, a linguistics major. “I don’t think text encoding is something you can understand without doing it yourself.”

My project reflects one of the defining characteristics of text — that it is constantly reevaluated and reinterpreted over time.

Seo worked with a compilation of short stories by Oscar Wilde, published 18 years after the writer’s death. For her digital edition, she focused on the editor’s preface.

“That preface gave me an idea of how Wilde was received some time after his death,” Seo says. “I primarily intended my edition as a tool to understand Wilde’s reception as well as his work, but I realized there was more to it. My project reflects one of the defining characteristics of text — that it is constantly reevaluated and reinterpreted over time.”

Emphasis on Preservation

Despite the students’ hard work, their digital editions are not currently viewable online. There’s a good reason for that.

“There’s an assumption that this is a direct pipeline into web publishing and it’s actually not that,” says Turnovsky. “It is an archival project — the students are creating a digital record of a printed source, which can then be used to create a website. But that’s a separate step.”

Why not skip the XML document and code directly for the web? Websites are too impermanent, Turnovsky explains.

“Converting something directly from print into a website is a terrible way to preserve a printed document,” he says. “It might look cool, but it’s not going to survive. An XML document, by contrast, is one of the formats libraries prefer for long-term digital preservation. This XML document can then be transformed into one or several websites or used in other ways.”

Turnovsky hopes students in his course come away with a deeper understanding of the impacts of past and present technology on text. He believes our interactions with digital texts will continue to evolve.

“When new technologies are introduced, people tend to imitate the forms they’re familiar with,” he says. “In the early print era, people still treated printed books as if they were manuscripts, illuminating them and using elaborate Gothic lettering. With digital texts, there has been a tendency to interact with them like printed books — but that will change. It’s still the early stages of this technology. It will take a while for our habits to adapt.”

More Stories

AI in the Classroom? For Faculty, It's Complicated

Three College of Arts & Sciences professors discuss the impact of AI on their teaching and on student learning. The consensus? It’s complicated.

What Students Really Think about AI

Arts & Sciences weigh in on their own use of AI and what they see as the benefits and drawbacks of AI use in undergraduate education more broadly.

A Love of Classics and Ballroom

Michael Seguin studied Classics at the UW and now owns Baltimore's Mobtown Ballroom. The two interests, he says, are more connected than they might seem.